![[Article Image] [Article Image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Yyll!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7b58a7cf-9fb5-4411-98c4-5e01f5f98acf_1600x800.jpeg)

Contrary to the predictions of political consultants and commentators, both of America's two major parties have continued to be politically relevant since the GOP broke a decades-long congressional losing streak in the 1994 midterm elections. The American government has been closely divided, with each party taking trifecta control of the government only a very few number of times. But even when they did have the trifecta-- that is control of the presidency Senate and the House of Representatives-- neither party passed much significant domestic policy legislation, aside from some tax cuts by Republicans and the Affordable Care by Democrats.

Fast-forward to the current moment, President Joe Biden has seen his approval rating among fellow Democrats fall recently, as some of his own voters have become dissatisfied. Biden's more left-wing critics have faulted him recently for not delivering on promises, and they've cited polls showing that the public supports their ideas like free college education or universal health care coverage, but they haven't been able to enact these policy ideas.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the partisan divide, the Republican party has many of its own internal divisions. And they're not just about Donald Trump, either. Polls have consistently shown that GOP voters don't really like any other Republican politicians besides Donald Trump, But Trump himself seems to have few actual policies beyond restrictions on immigration. In 2020, he refused to even create an official party platform for the Republican party. And more recently, the Republican Senate leader, Mitch McConnell, refused to say what sorts of policies that he would pursue if the GOP controlled the Senate.

It's a confusing situation. Republicans won't talk about policy, and Democrats can't enact it.

So what's going on here? In this episode, I was joined by Daniel Cox, director of the Survey Center on American Life, which is a non-partisan project of the American Enterprise Institute that focuses on original research and polling about cultural, political, and technological change in American society. And before that he co-founded the Public Religion Research Institute.

The video of our conversation is below. A lightly edited transcript of the audio follows.

Transcript

MATTHEW SHEFFIELD: Thanks for being here today, Dan.

DANIEL COX: Glad to be here.

SHEFFIELD: All right. So, there is a lot to talk about here today. Let's maybe first start off, you wrote an essay for the data site FiveThirtyEight talking about how Republicans, they don't seem to be concerned with majority support for their ideas. And they don't really talk about it much anymore. What do you mean in terms of policy ideas?

COX: Yeah, so I think if you look, and you mentioned this in your intro, at the Republican agenda, I think a lot of Republicans, independents, and Democrats would wonder just what Republicans are going to do if they win the House, and maybe the Senate in 2022, which seems at this point very likely. And you mentioned that Donald Trump, there was no platform in 2020. And I think that was by design. Trump didn't feel like he needed it. He, Trump, is the farthest thing from a technocrat as you could get, very little interest in the nuances of public policy.

And the only thing that the party seem to agree on, other than trying to overturn Obamacare is enacting tax cuts and which they did. But there's only so much, so many times you can do that. So, what else is the sort of far-reaching goal of the party? And I think that's a big question.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. Well, and at the same time though, the activists who form the core of the Republican party in terms of the people who run the campaigns, who write the materials, who knock on the doors, they do have ideas. But they don't seem to be rather popular, whether it's healthcare or some of the other areas, that's something you've written about recently in that piece.

COX: Yeah. Well, I think if you look at what animates the GOP now, it's not policy debates, it's certainly not things around Social Security or Medicare, healthcare, really, right? It's cultural stuff. During the Trump administration, all the outrage around Colin Kaepernick, not standing for the pledge of allegiance, now it's “critical race theory.”

These cultural wedge issues have really come to dominate what the activists are concerned about and talking about. And I think that it's really asymmetric in terms of what liberals and the Democrats are talking about and the things that they're interested in, and you think about climate change racial inequality, economic inequality, whatever they, there's a whole laundry list of stuff.

And Republicans, aren't not engaged on that for the most part. I mean, I think there's a couple exceptions. So like abortion is going to be huge this year with the Supreme Court ruling on it which could be seismic in its political effects, let alone the effects on the healthcare system, and decisions for many women.

And one of the things that we've seen in the past whether you're talking about abortion or same-sex marriage, is that it has pretty consistently animated conservatives a lot more than liberals. So if you ask about how much you care about this issue, right? The saliency question. We don't honestly ask it enough in polling.

We ask about where you stand on these issues and we, we get people to, to, share how they feel about these things, but we don't even ask them to actually care about it, or at least we don't do it enough. And conservatives consistently, rate these things as more important. They're more animated, their activists care about it.

SHEFFIELD: And that's true with guns as well. Guns is another big issue for that. But at the same time, the people, there are tons of organizations primarily in DC, but not just in DC that are out there, they want to privatize Social Security. They want to eliminate the Department of Education. And they have conferences and they get millions and millions of dollars to push these ideas. The Republican party doesn't want to campaign on them, it seems like. And people sometimes ask me why does that happen?

And I guess I'll ask you that. Why does the Republican party seem to focus on more cultural controversies than policies, would you say?

COX: Oh, I, I think the perception, which is, I think, which is somewhat based in reality, is that culture is an area where the, the playing field's tilted against them. If you look at all the changes over the last 20 and 30 years, it's been kind of the consistent march towards more liberal positions on a whole range of sexuality issues, premarital sex, same sex marriage-- all these things where-- marijuana legalization, it's been trending in a more liberal direction. And I think this is, happening on college campuses, too. And in businesses where you see Generation Z and millennials kind of trying to get changes implemented whether it's transgender issues, a whole variety of things.

And so I think there's this perception, and I think it's right among conservatives, that a lot of the culture is kind of stacked against them. And so you see them really, really aggressively trying to push back on these things.

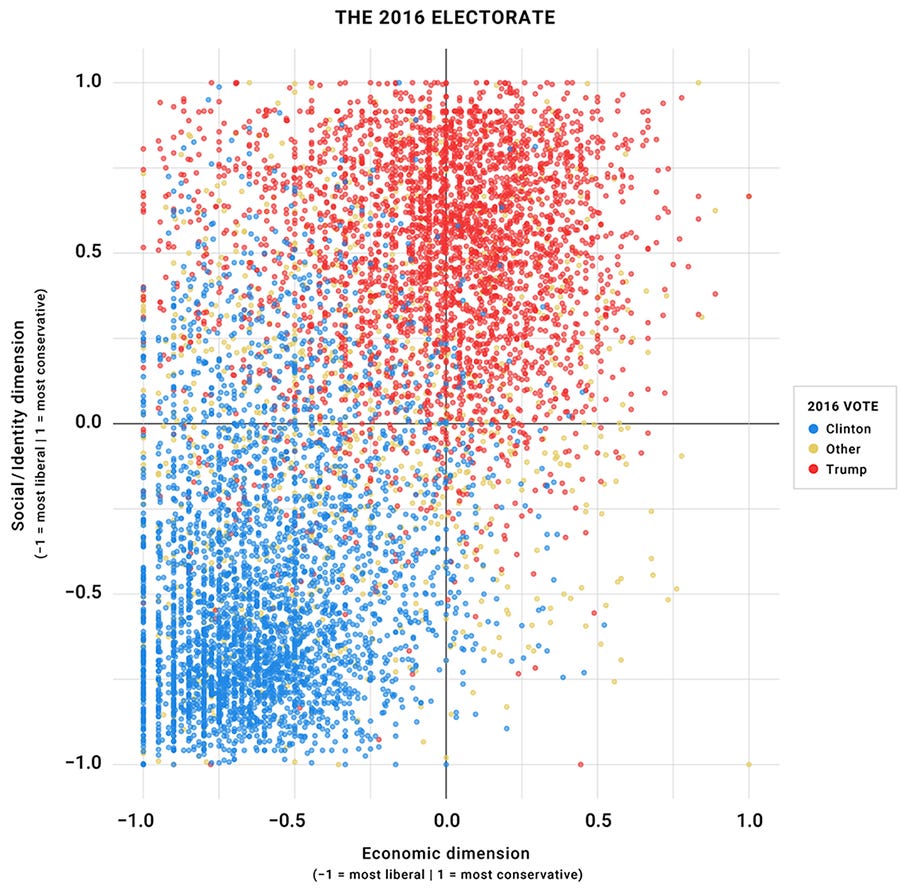

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. I think there's definitely a component of that. And one other thing, within academic political science, there's been a number of really interesting studies that have come out in recent years, looking at politics not as a left and right concern, but as an X and Y concerns, I've got up on the screen, there's several different scholars. This is one of several that I could have put up, but basically what they're showing is for those who are listening. So basically, how it's plotted on the graph is that you've got the X axis in the middle, that is basically what you want to do with the size of government and spending and things like that. And then the Y access or up and down is how you feel about cultural controversies. And the research that's come out has been pretty consistent showing that, a pretty large number of Republicans have economically liberal views.

And then a pretty large number of Democrats have viewpoints that are socially conservative. And so that's, I think is a huge component of why Republican politicians talk about this stuff a lot more because if you look on the economic side of things, there's not a lot of independents around the right side of the economic spectrum. And a lot of Republican voters themselves are on the left side of it. So you're more likely to find people who are receptive if you talk about cultural controversy, it seems like. What do you think of all that research? I'm sure you've seen it.

COX: Yeah, no, I, I agree with it. I think we probably do ourselves a disservice by using labels like conservative and liberal so often, even in polling, whether you have a five-point scale seven point scale is that a lot of folks, don't really understand the labels, right? You certainly get a number, a fair number of African-American voters identifying themselves as conservative because they, they see themselves-- and they are theologically conservative. A lot of them belong to more conservative denominations and that's kind of how they see themselves. But if you look at their views on a whole range of economic policies, they are pretty consistently liberal and kind of mainstream Democratic.

So yeah, people will sort of have different valances when they think about these labels. And for a long time, I think that the liberal label carried some baggage. And so you had people who ostensibly were liberal, but didn't want to accept the label. So you had that progressive liberal came in, and now you're saying younger people, I think more likely to adopt that.

But yeah, I think that there's a lot of truth in there. And I think to the, to the extent that we don't capture that, in our polling and, and, and we talk about it and when we're debating this stuff, we aren't telling how we can't tell the complete story.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. And that's, a consistent thing that I've been thinking about a lot lately is that people in the news media gave people the wrong impression of what polling can do and what it can teach you. And people just thought, oh yeah, it will tell us exactly the margin of victory of Candidate X or Issue Y, but that's not really what the point of it is, right?

COX: Right. Yeah. I think we have wildly problematic expectations about what polling can accomplish, and what it's designed to accomplish. It wasn't designed to predict the future, pollsters aren't oracles, but we can look at a certain set of questions, and depending on how well we write them, depending on how well people are able to interpret them and willing to answer them. We can tell you what's going on right now and what people are thinking about Issue X or what their behavior is. But for predicting human behavior, that's incredibly difficult. It's complex, it's influenced by a whole variety of different sources including the people all around you. We often attribute behavior entirely toward, to your individual characteristics.

So if you're White, if you're wealthy, if you live in a rural area, these are all individual attributes and they are determinative of various political behavior, but you know what else matters? The people in your social network, people around you, people you live with. And that we don't measure often enough.

I've done a lot of work measuring social networks and trying to understand how that matters. And people with only Republicans in their network behave very differently than the people with only Democrats in their network, in terms of not only how they vote, but what they can believe.

I wrote recently looking at willingness to get vaccinated. And there's been a whole host of stories about how it's been so politicized, and it has. Republicans are, and Republican-leaning counties, far less likely to be vaccinated than those in liberal and Democratic-leaning counties.

But you know what's a stronger predictor than ideology or party is whether you have friends or family that are vaccinated. If your social network is almost entirely including people who are vaccinated, the odds that you were vaccinated is extraordinarily high. So I think those parts of that we don't typically measure because it's expensive and it's difficult.

And so I get it. But I think it's important that we understand that these things matter as well. So not just these individual attributes, but sort of the entire sort of social context.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, well, and, and even something like that, it's often hard to distinguish between cause and effect as well.

And so even if, you're running a regression analysis or something like that, that doesn't actually necessarily tell you whether something was a cause or a coincidence.

COX: Sure, there's selection effects, right? The kind of Republicans who would have a lot of Democratic friends and family are probably very different than the kind of Republicans who would have no Democrats in their social network.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, well, and one of the other issues, I think that's not talked enough about in the discussions of polling that we have in popular media is that we're relying on self-reporting and in the field of psychiatry or psychology or sociology, there are people who do nothing but analyze the problems of self-reporting and how it can be unreliable.

For the audience who may not have heard of any of these issues, can you walk us through what some of why self-reporting can be a problem?

COX: Sure. So for something like religious attendance or voting behavior, these are, and have traditionally been viewed as socially desirable behaviors.

Right? So, we, at least historically, traditionally we wouldn't look as highly on someone who didn't attend religious services or didn't vote, didn't participate in politics generally or civic life. And so, people might inflate their actual-- and we don't, we don't say lie-- but essentially, they're misreporting what they're doing.

And there's been a variety of explanations about why that happens, but the most important for people to probably know is this idea of social desirability bias, that you want to sort of present the most positive idea of yourself. And part of that will be how you present yourself and how you answer these kinds of questions, I think is another really important part of this debate, I think one of the things that we're, we're all kind of struggling with is, are we getting the right type of folks? So there, there are some folks that are just harder to get to answer survey questions or surveys at all. And one of the things that I think that happened in both 2016 and 2020 is you had folks who were just unwilling to participate in surveys.

And, and this always happens. But I think what happened in those two elections is these folks were instead of having kind of more neutral political opinions or an aggregate, they cancel each other out. They actually tended to be much more strongly supporting Trump and something that I looked at, after the 2020 election was just who these people were.

And one of the things we found is that people who were kind of socially disconnected, civically disconnected, folks that were less likely to participate in surveys, disproportionately supported Trump. So if they weren't included in samples, we weren't interviewing them. We weren't hearing about their views and voting preferences, leading us to I think miss or at least leading some of the surveys ahead of the election to understate or undercount Trump's support.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. I, the other thing also is that a lot of times, when you ask people to assess their ideology or you ask them, do you support policy X? They might not even know what policy X is, but they might give you an answer. And that can be very problematic. And so, so, when people do party identification polls, or asking people, are you a conservative or liberal or whatever these, these can be very inherently problematic and it's tough to know, what you're getting with the results, even if all the numbers are statistics, the formulae are correct. The X factor is you don't know what the person on the other end of the question, what they actually think.

COX: Yeah. Right. And I don't want to spend the whole episode talking about the problems of polling. I think in general it's pretty accurate, but, but I think you're right to point out there are limitations.

And just recently the Pew Research Center published this report that showed that there's something. I think it's called acquiescence bias, right? It was just folks wanting to be agreeable and helpful. So if you ask them an agree or disagree question, they're more likely to load into the agree side than if you ask the question differently. So if you said should we have a foreign policy posture that prioritizes, showing the strength or should we be more diplomatic and working with allies?

And if you ask those as agree/disagree, you get a majority of people saying, I agree with both of those and that, but if you pair them against each other and ask, are you more closer to this or this, you get a pretty significantly different, different story. And so I think, yeah, that's important. And the other thing that I almost always tell people when you're looking at any poll is don't look at it in isolation, you should try to the best of your ability to sort of see what else is out there on it. Like if you're looking at questions on abortion, what else has been asked, about this issue? And a lot has. So you can get sort of the broader context of survey results. And if folks, if asking them differently, look at how people are asking questions, you should not never trust any poll where the pollster's not willing to provide all the information about how the poll was conducted the methodology and the actual question wording.

SHEFFIELD: Very true. And speaking of Pew, one of the projects that they do and they do a lot of great polling of course. But one of the ones that they do that's fascinating, and I don't think gets enough pickup is they do a survey every few years with a massive, massive sample where they try to subdivide the coalition members of each of the two major parties.

And what they find is often very interesting. And it should be looked at a lot more in, so I'm just going to put up on the screen. They do with them for both parties in, up on the screen. We'll talk about Republicans, just very brief. So they've got different groups here, “Faith and Flag” as Pew calls them, is basically people one would associate with the traditional religious right. Like they think that America is a nation for Christians and Christians should rule America. And they also have economically Conservative beliefs as well, but faith is more important to them than anything else. So that's 23% of the Republican party.

And then 15% of the Republican party is “Committed Conservatives.” Those are people who are more like, let's say Mitt Romney or Liz Cheney, people who are focused mostly on government waste. But they have some culturally conservative viewpoints as well. And then below that there is “Populist Right,” 23%. Those are people who tend to be very skeptical of corporations, businesses, they want more regulations. So they have generally left of center economic viewpoints, but they like the Republicans' stances on abortion or on same-sex marriage or transgender rights.

And then we've got 18% “Ambivalent Right.” Those are people who generally speaking are, they're just barely Republicans. They tend to be more moderate libertarians. And then we got “Stressed Sideliners,” which is people who don't have a lot of interest in politics. They just don't pay attention to it a lot.

So that's the Republican side. And then over here on the Democratic side what's different, and I'm going to just show it very quickly here for those watching. So for Republicans, “Faith and Flag,” those are people who have pretty far-right economic ideas and religious social conservative ideas and “Committed Conservatives”—so people who have strongly ideological viewpoints in the Republican party are, in the Pew data, a very large number. We've got 38% of the Republican party has very strong ideological preferences.

Whereas if you look on the Democratic side of the aisle, the people who are the most ideological are the “Progressive Left.” Those are people who are Bernie Sanders hardcore devotees, that's only 12%. And then you've got “Establishment Liberals.” They tend to be more moderate on economic questions or sometimes have even some conservative views.

And then you've got “Democratic Mainstays.” These are people that have liberal economic viewpoints, but more conservative or moderate social views. And then you've got “Outsider Left” and I'll put links up to all the different groups so people can get the details on it, but what's been interesting in watching the interplay within the Democratic party as Joe Biden came into office, is that it seems like a lot of progressive activists seem to overstate just how big they are within the party. Would you say that?

COX: Yeah. I think there is a healthy center in the Democratic party. And, people like Joe Biden, that's where he's been for most of his career. Now he's moved pretty significantly to the left, which I think is often not acknowledged, particularly on the left. If you look where he was in 2008, when he was Barack Obama's running mate his views were, considerably more to the right, more to the center and the whole party, whole Democratic party has moved to the left.

And one of the things that's really interesting is for a time-- and this is a theory that I've bought into as well-- is that, we talk about asymmetric polarization, where the Republican party had moved further to the right than the Democratic party had moved to the left. I think that's just not true anymore.

I think we're seeing both parties kind of move away from the center. I would say Biden is a more moderate candidate and I think the Democratic party is more effective in, in putting the people that it perceives as most electable and that tends to be moderates and the GOP I think has, does not have the same kind of control.

Just look at Trump. Wasn't even a Republican for a long time, at least until recently. And then he, ran the tables. And so I think like that, there's a pretty, there's a pretty significant difference in the amount of control. And the, and the other thing is, is there's a really important constituency within the Democratic party that is more moderate conservative, and that is Black voters. And also to some extent, Hispanic Christians.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. Well, and that's who the Democratic Mainstay group largely is in the Pew data, there are people who don't support transgender rights for instance, or they may not even currently support same-sex marriage or things like that or may want to see abortion restricted or, in various ways.

COX: Right. And there's, there's, important cross pressures among some of these communities, too. If you look at the African-American community, and particularly Black Protestants, on a lot of these issues, whether it was gay rights, transgender issues, they've, they've been less supportive historically. They were probably the last group in the Democratic coalition to come around on same-sex marriage. And there's still some significant opposition there.

When you look among Hispanic voters who have traditionally been a little more Democratic leaning, although that's changing, abortion, right? If you look at Hispanic Protestants and Hispanic Catholics, they were far less supportive of legal abortion than that sort of mainstream Democratic voters.

Some of these folks, while they were very supportive of the economic policies of the Democratic party, on some of these important cultural questions, there was some tension there. And I think that has actually helped the Democratic party from moving too far to left, although I think certainly some people would say that they have been on certain questions, but I do think that both parties have an activist base that try to pull them to the poles. And to the extent that they are successful, they can, they try to stay rooted in more towards the center to appeal, to, to large number of voters as possible.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. Well, and I think one area where there is an asymmetry is that when you look at the media that is produced by the activist left and the activist right, generally speaking, the activist right is trying to persuade other Republicans to their ideas.

That's what talk radio is for is to say, this constant cancellation attempts of moderate Republicans, they're always going after the “RINOS,” Republican in Name Only. You're not a real Republican, unless you're, a reactionary or conservative Republican, that's what the bulk of the ideological content of more right of center media is.

Whereas on the left of center, it's tending to be more the activist left talks to itself. They don't talk to the rest of the Democratic party. They're making this stuff for themselves. So, like using different terminologies then.

COX: Right.

SHEFFIELD: Like this whole Latinx thing, or even this idea that, a lot of Democratic activists, progressive activists didn't seem to understand that Black voters actually did like Joe Biden in 2020. They couldn't believe it. They wouldn't believe it. They wouldn't accept it.

COX: Yeah. And I think when you think about the ideologies of both parties, it, it is complicated. And I think one of the problematic things that's that's happening right now on the right is conservatism is, has become associated with loyalty to Trump. So what Trump espouses becomes conservative orthodoxy, even when it's not consistent with what most of us would consider a conservative ideology. And there's, there's this recent paper by Dan Hopkins and Hans Noel that finds GOP activists are basing their perceptions of conservatism of various legislators on how closely they are aligned to Trump.

So you have some very conservative members like Liz Cheney or Pat Toomey from Pennsylvania who are viewed as being more ideologically squishy. But if you look at their voting behavior and their records, that they are nothing if not very conservative, but Trump has redefined what conservatism means.

SHEFFIELD: Oh yeah, no, he has. And that does go to another point and that is that because Trump doesn't really talk about policies that much. The only thing he talks about now is the 2020 election pretty much. And these are not policies. This is the rise of identity, that to support Trump isn't to agree with his policy position, because he doesn't have any, it's to see him as your friend kind of in a lot of ways. And now you've, you've done some interesting research on the idea of a friendship as within the American society and in particular, in regards to male friendship. And I think that that may play a role in terms of why people regard Trump as, he's their friend, he's their guy that they want to, have a joke with and have a beer with or whatever. Can you talk, tell us a little bit about some of what you've been researching.

COX: Yeah, and I think this does, it, it hooks, it connects to a lot of our, our politics if not directly, but I think importantly in, in indirect ways.

So when I see people sort of saying, voters on the left saying we don't understand why Joe Biden's not more popular. Look at all the stuff he's done. Look at the recent jobs report. He should be kind of cruising and not stuck around in the low forties in terms of his job approval.

And I think, there's some sense of well, what's going on? Why are people so miserable? And certainly the pandemic is playing a large role. But I think also the decline in social capital is really, really important.

If you look at what makes people happy, it's not having their preferred policies passed, certainly, money matters, but also, the amount of social support that you have, the social solidarity you feel among people, at your neighbors, people at your church or congregation, being married is associated with a greater feelings of satisfaction and happiness.

And we know the marriage rate's declining, civic engagement's declining, participation in a whole variety of religious services was declining well before the pandemic started. So we know there's all these things that are happening, and the report that I released a few months ago, we looked at the education divide.

And what was happening is that folks without a college degree are suffering far more than those with a college degree. And these are the folks that are becoming more likely to be supportive of Trump.

SHEFFIELD: Can you define what you mean by suffering though, just so for--

COX: Feeling low feelings of loneliness, if you look at drug use the inability to hold down a job, right? The whole, all these things that sort of connect us to civil society. They are, for whatever reason, no longer attached to you. And in fact, Obama's sort of famous gaffe where he says, 'folks without a college degree cling to their guns and religion.'

Well, actually it's the college educated folks that are more likely to be attached to religion. If you look at membership rates of religious congregations, it's the non-college folks that have seen the most precipitous decline, not, not the college-educated folks. So again, all these things that are pressuring not just economic pressure, but social pressure as well that they look around and like, they just feel it viscerally, like my life's not going that well.

SHEFFIELD: I feel abandoned. Yeah,

COX: For sure. Right. They feel economically abandoned, that the institutions that they used to find support, whether they were unions or religious organizations or civic organizations, and their society are no longer there either. Or at least not in the same way that they were.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, well and here's an interesting paradox, is that to some degree, I think you could argue that the conservative takeover of the Republican party, it also made it less likely that the Republican party would stand up for the interest of the people who voted for it in terms of healthcare or Social Security, or like the minimum wage.

So in the past, Republicans and Democrats, both kind of a greed to some degree or another on the minimum wage, for instance in terms of the parties. And when you look at the voters, the Republican voters still haven't changed. Like they still would like to have a higher minimum wage.

But they're not getting it. And so that's, what is interesting about the rise of Trump is that Trump. People, people forget that in 2016, Donald Trump said, I'm I support raising the minimum wage. I support, Canadian healthcare. He said that several times. And so a lot of Republican voters, or, let's say Republican leaning voters, they saw that.

And they were like, finally, here's somebody who is going to talk about what I want the Republican party to do. And that was how Trump won the primaries. And everybody on the activist, more conservative side was like: 'Oh no, no way. No, one's, that's never going to happen. Republican voters won't go for it,' but they were wrong.

COX: I think something else, that, that, that happened with Trump is, he very clearly articulated and identified who he was against. I think that all this stuff of ‘well, we don't know, Trump didn't lay out an issue agenda who was on associated with particular issues, issues per se.’ But he said 'I'm going to take on these elites that you hate that have been screwing you over. And that really resonated.

And I think it's one of the real problems with tribal politics. We talk about that a lot, right? We're politically polarized. We're in these two tribes that don't talk to each other. We don't like each other.

But that to me is not the most serious problem there. The problem is that that membership in our tribe is defined not on a shared set of beliefs or values. They're defined by how much you hate the other guy. And that's really what I think where we've, these have gotten off the rails.

There's some great work by political scientists, Liliana Mason, and what she identifies is there's been a kind of a social sorting and stacking where multiple social identities are reinforcing the political cleavages. So if you're White and an evangelical Christian, you are much more likely to be a Republican today than that than was true a couple of decades ago, if you're young and you're atheist, your odds of being a Democrat are astronomical.

And so I think as these social identities, and the same is true with rural and urban, that we're seeing the same some polarization along geographies. And I think that's, allowed this kind of really toxic tribal element to to take off, right. That, that, that so much of it is, is based on social identity and who, who, not who you are, but who the other person is not.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. Well, and now that was something that-- you were one of the few people who noticed that in 2010 with the Tea Party movement, you and a couple of colleagues when you were over at the Public Religion Research Institute. You guys did a poll about the Tea Party and at the time, a lot of people in the news media, there were these endless series of articles about how the Tea Party was, it was the libertarian moment in American politics. And this was this was a revolt against spending and things like that. But that wasn't what you guys found, was it?

COX: No right. It wasn't this kind of organic movement against larger government. If you look during that time period, in fact, views about the size of government, I don't think changed all that much. We do see kind of predictable shifts in, in views about the role of government society, there's a method, something that the scientists call thermostatic opinion.

So when Republicans are in control of government and enacting policies to reduce the size and scope of what it does, the public generally becomes more supportive of increased government involvement or activity. But when Democrats are in charge, public tends to be more supportive of reduced government spending.

But philosophically, right, most Americans are, are pretty supportive of an actual government. If you look across a range of different issues, they may not trust government. They may think the politicians running it are corrupt, and not have a very nice thing to say about the bureaucrats that are administering some of these policies, but they still, they still support what it's, what it's doing.

Support for universal health care garners a majority of support, medical leave, parental leave. Like these things are all pretty popular. Increasing the minimum wage we talked about earlier, that's popular as well. And so, there's simply not that many sort of people that are ideologically committed to smaller government and like libertarians they're very, very small.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. Well, and in your report about the Tea Party specifically, though you guys found that so 55% of people in your survey had said that America is currently a Christian nation and then 37% said that it had been in the past.

Literally only 7% of Tea Party of respondents said that America had never been a Christian nation. And that was, it was a significant finding, I think. And because, it showed that this was, in very large, to a very large degree kind of, a Christian identity movement. And, and people didn't see it that way at the time. Why do you think that was? Or why did they, how did they miss that?

COX: Yeah, well, I think that some of it is about sort of the kind of promotion and perpetuating narratives of a lot of the Tea Party organizations. So they were drawing a lot of their supporters from current or former Christian right organizations for the movement. And I think that was a big part of why they were successful. People were already invested in being active in politics. So this wasn't like a new group of folks they had to sort of bring into the system. These are people who have been active for a considerable amount of time already. And so I think that that narrative that got set and then the media were difficult to dislodge. Once they have a narrative, they tend to run with it.

SHEFFIELD: Hm. In terms of the identity it's, it's interesting also that you see in the, speaking of the press I guess, you see a lot of the discussion, it seems like most of the discussion of so-called identity politics tends to be a examinations of whether it exists in the Democratic party or not.

And like, there's just no discussion about. Where did identity politics were effectively invented by the conservative movement in the 1950s? That, or let's say Jerry Falwell and friends in the 1970s. That's pretty much what it was for the most part.

COX: Yeah. I find it. I find it kind of unhelpful, the whole idea of identity politics. It effects both, it's part of both parties, it's the same thing with cancel culture, both sides do it and they just don't like it when their side's canceled and the other side's not. And so, yeah, I think in, in terms of, of our political data, something that'd be much more helpful is trying to get underneath some of this stuff.

Like it's the same thing about with critical race theory. If you get underneath it and look at some of the ideas, right? Like you could actually get to a place where wow, there's actually some consensus here. Same thing with sort of free speech right there. The majority of Americans are concerned about free speech and support a whole variety of different free speech protections.

And when it comes to teaching race in schools yeah, most of Americans, a poll we conducted in the fall found an overwhelming majority of Americans support teaching that the Civil War was fought over slavery. The negative treatment of Indigenous peoples by the federal government, Japanese internment and all of this sort of, the darker parts of American history. Americans are supportive of students learning about.

And the areas where there is some disagreement, they tend to be sort of newer sort of new ideas. So like the idea of White privilege, that engenders a lot of division. And it's not even a majority of Democrats who support that. So I think that again, for the sort of the basic stuff, again, there's a lot of areas of agreement and commonality and, and, if we can sort of cut through that stuff.

I know actually a lot of politicians don't want to because they're using it to their advantage. And a lot of media people don't want to either because it gets new viewers. But I think like in terms of solving policy debates, we can do that a lot more effectively if we can just come to the table and say, let's, let's break this down and see what we're actually talking about here.

And that's one of the reasons we didn't ask about critical race theory in that poll, because people don't know what it is, and there's so many misconceptions about it. But when you asked about some of the constituent parts or the underlying ideas about how we treat race and how you teach about it, you do find a fair amount of agreement.

SHEFFIELD: And that goes to the problem of self-reporting that you have to understand the question and the questioner has to understand you, and it's difficult. But it does go to a larger issue. And that is that when you look at, if you look at the biggest major social change that happened in the United States since the civil rights bills of the 1960s was, the, the movement for legalizing same-sex marriage that was such a significant and important movement.

And yet I feel like in the political analysis and punditry business, people don't talk about it enough. And if, especially if you're a progressive, you should be looking at that as a model because when they got started, the Democratic party was terrified of this issue.

They did not want to touch it. They told gay rights activists to go away and don't ruin their prospects. But what they did instead was that they, they built a case for marriage equality from a variety of perspectives. So they didn't demand that you accept everything one particular way.

So in other words, if you thought that there was a religious region to support same-sex marriage. They didn't care if you thought there was an economic reason to support it, or they didn't care, whatever motivation you wanted to have, they were fine with it. And that's why they won ultimately.

COX: Yeah. I I actually wrote about this a while ago. And the basic argument I have is that it's not replicable. Like the coalition and the strategies that allowed the same-sex marriage advocates to, to succeed, if you're looking at abortion or immigration reform and there's just not less, not really transferable is the idea that, so many people know someone who's gay or lesbian and gay and lesbian people are born into liberal families. They're born into conservative families. They're born to Asian, Hispanic, and Black families. And so, just the fact that you aren't able to really socially segregate yourself effectively the same way you can politically or along any other sort of social identity was really important.

The other thing is that even back in the early two thousands, when I think support was, it was probably in like the forties, most Americans thought that same-sex marriage was inevitable that eventually it would be legal. And that is something that people have not thought about it a lot about this other sort of more cultural controversial legislation, that it's inevitably never really gonna happen.

And so, there were sort of unique instances that the same-sex marriage advocates had that, that I think other activists, on either side or issues don't have.

And so I think it was a pretty unique moment. And the other thing is really interesting about it, is that liberals didn't care that much about the issue at the time. It was not, it was simply just not a galvanizing issue. We looked at it like we're millennials, we're back in the, in the two thousands, it was talked about as this was going to be the issue that would, bring this generation into your sort of political activism.

And yeah, they were largely supportive, right? They had people in their lives who were gay and lesbian who they loved, but it just, it wasn't animating in the same way as it was for the conservative Christian.

SHEFFIELD: But on the other hand, the thing about like guns, for instance, for the coalition in support for opposing firearms restrictions, that actually also is cross-cutting in terms of, there's people of all races have guns, people of all economic backgrounds have them.

Now granted, there is a particular subculture that is, especially interested in guns, but that's, I think that's an issue. And for a long time, the NRA pursued a strategy. That was bi-partisan actually, they were big supporters of Harry Reid for instance, and he supported them, but then they kind of--

COX: They were rural Democrats.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. Well, and so, yeah, I mean it, and you can maybe that's maybe that. That sorting sort of moved away from that. But I don't know. I, I still think that there are ways that if people do care about specific issues, that at the very least they need to learn how to formulate an argument for them that doesn't pack in all these other assumptions.

So in other words, if you want to support keeping abortion legal, then you need to figure out ways, multiple justifications for it. Or, vice versa. If you want to persuade somebody who's not religious, that abortion is wrong. Well, then you probably need to make non-religious arguments that abortion is wrong.

And that's something that I think that specialization of media has kind of gone against that. It's easier to have a small group of people who agree with you a hundred percent than it is to have a much larger group who agree with you on 70%.

COX: Yeah. And again, the social sorting stuff is really strong and understandable in a way. So if you look at people with sort of diverse political networks, they argue more about politics. They're less comfortable talking about politics, and that makes sense.

If you have a diverse set of people, you're, you're talking about these things. Yeah. So at some point someone's going to push back. And that, that can be an uncomfortable place, but we should get a lot more comfortable with it. It's so much more effective to have those kinds of discussions than throwing grenades around on Twitter. Which solves absolutely nothing.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. Well, it's certainly not a way to get your, your idea to become law. But ultimately the incentives that both parties have to do what would be better for them in the longterm, if Republicans wanted to have more voters, if Democrats wanted to have more voters, they would do certain things, but they don't do them.

So if the Republicans wanted more voters, they would adopt more economically moderate positions, and try to find ways of appealing to people who are not, White, theologically conservative Christians. And then if Democrats wanted more voters, they would have to spend more time on media explaining their ideas. In other words, there's a lot of casual support for Democratic or progressive ideas, such as single-payer, single payer healthcare. The public agrees with a lot of progressive ideas, but they don't really, they're not very passionate about it. And Democrats don't seem to want to build up that passion for some reason. It's interesting how neither party seems to do what they should if they actually wanted to build a lasting legacy.

COX: Yeah. It's really interesting that, the the lesson of the 2020 election was actually, you don't need to do that necessarily, right? Like Trump improves his performance among Hispanic voters. And people are left scratching their heads, like what is going on? And, I don't think it was about policy for the most part. There's, there's other things that are sort of cultural touchstones too, Hispanics remain one of the groups most likely to still believe in the American dream, the importance of education, they remain, along with Asian Americans, among the most optimistic groups about the future of this country.

And, when you have liberals were saying, oh, no, things are awful. And I think it just, there's sort of a cultural disconnect. And I'm not saying that that's the only thing going on, but I think it, it goes to the point that, even if you, surgically developed a near perfect issue agenda to appeal to, the widest swath of voters, I, I don't think it necessarily you'd end up where you think you would.

And then the other thing to remember too, on some of the polling stuff is that we often poll of the adult population, and the 18 plus. But that is not the voting population for the most part. Depending on the election, you could be anywhere from like 25% to maybe two thirds.

And there's been some analysts on the left that have actually noted that when you look at issues with people are voting for issues on referenda, that it generally gets a lot lower support than it's been the polling results show, even when you're polling voters. And this happened, I think, I think most memorably on Proposition 8, right? It was the California proposition in 2008 to ban same-sex marriage or write it into the state constitution. And it was adopted. Despite the fact that polling showed most Californians wanted same sex marriage legal. And so there's this sort of differences there that I think are notable.

SHEFFIELD: And it's also a question of how, it's possible that those polls were correct in terms of who supported it, but in terms of the intensity, the people who, were against Proposition 8 may not have cared that much about it. And so these are all questions that, it is a bigger problem for Democrats than Republicans that Republican voters tend to be more engaged in politics, more interested in it, more entertained by it. Whereas Democratic voters see politics, except for that small percentage of progressive left people that I talked about. They tend not to follow politics as much as Republican voters.

And so it's interesting that they focus so much, Democrats focus a lot on, 'Well, we need to make voting easier.' And they do it because they presume that 'The people who aren't voting agree with us,' but at the same time, they're not trying to say: 'You could vote, you had no problem with voting, why don't you? How come you're not showing up?'

Because the reality is that, in a lot of states, even with the fewer restrictions on voting and participation in 2020, there were still tens of millions of people who decided not to vote.

COX: Yeah. Right. And there's been some research that has been showing that regardless of who votes, if you increase the voting by 10%, 20%, it doesn't necessarily advantage one particular party. I think there's this idea that, that when more people vote, Democrats do better.

SHEFFIELD: But not necessarily true.

COX: Right. It's not necessarily true. I think it's, it's increasingly likely to be maybe more advantageous to the Republican party if a lot of these more disconnected voters, who, who supported Trump, right? They were not hardcore Republicans, but they were kind of disaffected and they supported Trump, if they stay there, they sort of stayed in Republican-leaning.

And if the party continues to attract sort of the non-college folks who are not as likely to be regular voters, then making it easier may actually help increase the number of Republican votes. So it's, it's, the story isn't even clear.

SHEFFIELD: For a long time, historically, people who did absentee voting were Republicans, but they were more likely to use it than Democrats. And so yeah, these questions don't really get discussed a lot. It's like, there's just this blanket assumption by both parties that, that if these laws are passed, that it will help Democrats or these other ones are passed that it'll help Republicans, but it's just not necessarily true.

And at the same time, the percentage of non-voters, those non-voters, those non participants, it's a very diverse group, both racially, religiously, in terms of age. And they all have different reasons for not participating.

And that's kind of what happened with Trump. It seems like that Trump brought out a lot of, of people who didn't like either party, but especially didn't like the Mitt Romney style Republican party, because they saw it as that was the guy who laid off their father when they were a kid. 'And I I'm not going to vote for that. But I will vote for a guy who stands up for the working man.'

And that was the dilemma that Trump solved for Republicans, it seems like to some degree. Whereas with Democrats, they haven't tried to figure out very much in terms of why the people who might lean their way don't show up for them. I don't, I don't see a lot of discussion about that.

COX: Yeah. I think the biggest thing that Democrats realize is actually you need White voters, right? Like there's, there's been a number of scholars or activists that I think viewed Obama's election as, as a kind of a tipping point where, the 'coalition of the ascendant' where, you know, Black and Brown voters, non-religious voters, young voters, women voters, college educated voters would push them past the finish line and they could kind of ignore the White working class voters that were mainstays of Bill Clinton's coalitions.

And that's wrong. That is absolutely wrong. And I think that the biggest thing that the party leaders I think have come to grips with is, you still have to fight for, for these voters. And I think that's a good thing, right? I think I actually think it's a good thing that Trump is able to attract more Hispanic voters. I think the worst thing that can happen is we become a two party system with White voters supporting one party and non-White voters supporting the others. I think that that is a really, really bad place for us to be democratically speaking. So I think both parties should compete for, for every vote.

And I hope they do.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, well they certainly should. They certainly should. And it would be better if they did. All right. Well, I, we could certainly go on a lot longer, but I don't want to keep you here for too long, so I appreciate it.

Let me just give people a plug for you. So you're on Twitter at dcoxpolls, and people can check you out there. And then what is the address of the Survey Center on American Life? Tell us that one.

COX: AmericanSurveyCenter.org.

SHEFFIELD: Okay. All right. Well, great. Appreciate you joining the show today and I'll make sure to put a link to all that stuff in the show notes as well. If you want to send me any of your more studies or something that you want people to see that we discussed be sure to do that as well.

COX: Sounds great.

SHEFFIELD: All right. Well, thanks for being here, Dan.

COX: Thanks for having me.

SHEFFIELD: All right. Well, so, that's the show for today. And these are topics that we're going to be returning to a bunch throughout 2022, looking at the limits of change within each political party and how, and whether or not the parties understand their own voters and how to make change. We'll be going on that for quite a bit. Please join us.