Episode Summary

Politics is a battle over elections and policies, but underneath it’s really a battle over stories, the cultural myths that shape our sense of identity, power, and possibility. And few stories loom larger in the American imagination than the saga of Tupac Shakur, the rapper and actor whose influence continues to resonate across the globe nearly 30 years after his death.

It’s easy to see why. The problems of poverty, racism, capitalism, and inequality are as present today as they were when Tupac and other early hip-hop musicians began telling stories that no one else would.

Talking about all of this with me today is Dean Van Nguyen. He’s the author of a new biography of Tupac Shakur called “Words for My Comrades: A Political History of Tupac Shakur” that highlights the political legacy that was lost when the emcee was gunned down in the streets of Las Vegas in 1996.

While today’s rap industry has largely been absorbed by the capitalism its pioneers once resisted, the radical spirit Tupac embodied still echoes—sometimes in unexpected places.

One of those places is Donald Trump’s political movement. In a bizarre turn, Trump has increasingly styled himself as a hip-hop folk hero—and, surprisingly, more than a few rappers have gone along with it. This is a conversation about symbolism, masculinity, memory, and resistance.

The video of this episode is available, the transcript is below. Because of its length, some podcast apps and email programs may truncate it. Access the episode page to get the full text.

Related Content

A flashback look at how Donald Trump reached out to hip-hop stars to push his 2024 message

Nicki Minaj, Snoop Dogg, and toxic gravitation: How reactionaries bond over mutual narcissism 🔒

Why the decline of the black church is helping Republicans reach new voters

Doja Cat and the lies we tell ourselves about sex and race

Many Black Americans don’t like Democrats, but they loathe Republicans even more, which disdain will prove stronger?

Audio Chapters

00:00 — Introduction

05:53 — Tupac’s continued global resonance

09:14 — The origins of hip-hop and its commercialization

11:35 — Tupac’s legacy of contradictions

18:41 — The Black Panthers’ influence on Tupac’s mother

23:50 — Masculinity and gender within hip-hop

29:06 — Gender and sexuality in the Black Panther Party

35:56 — Obama and Trump in rap

39:12 — Former Panthers still have hope for the future despite Trump

41:31 — Trump’s 2024 campaign reached out heavily to hip-hop artists

46:22 — ‘Coolness’ as a non-political voter persuasion method

50:22 — How Van Nguyen brought oral history into his book

58:19 — Eazy-E, another political West Coast emcee

01:01:55 — The meanings of ‘thug life’

Audio Transcript

The following is a machine-generated transcript of the audio that has not been proofed. It is provided for convenience purposes only.

MATTHEW SHEFFIELD: And joining me now is Dean Van Nguyen. Hey, Dean. Welcome to Theory of Change.

DEAN VAN NGUYEN: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. So this book is, it's a really important book, actually, I think especially because it's connecting a lot of ideas that got started during the life of Tupac Shakur, obviously by him, but also by other people.

And he's a guy that continues to remain relevant despite having been killed decades ago. And you write in the introduction of the book that you see him as America's last revolutionary figure. Tell us about that.

VAN NGUYEN: I think America actually isn't a nation that tends to create these. Figures. It's been a, a stable political, system for quite a while now. So I think when you see where Tupac's icon has resonated mostly across the world, and it tends to be in countries that have histories of colonialism and colonial oppression and anti-colonial uprising such as my own country, which is Ireland and nations that have suffered brutal dictatorships and have had uprisings against that and things of that nature.

So he, I think his icon has grown to, to be almost this, almost like avara figure where he. He represents [00:04:00] ideals, like to see his image ignites certain feelings within people or certain ideas within people of, revolution and resistance. And I don't think there's actually too many Americans as you could actually say that about.

Yeah, I think if you got, like there was, of the, figures in the book as well who's icon, who's I comparing to a little bit is like Bob Marley. Che Guevara. So, yeah, I think I, I can't really think of anyone who's come since him that really matches that, that that symbol that he's become, side of the us.

SHEFFIELD: If we expand outside of the us other non-American figures can you think of people after Tupac generally that are, that widely known and recognized as revolutionary icons?I think he's certainly, I think, the single most recognizable icon that hip hop produced. I think maybe the other one might be Eminem, but I'm not sure that when people, recognize who m Andm is when they see him, but he, doesn't ignite the same se a set of principles that like, that Tupac does.

VAN NGUYEN: S so, yeah, and I think that he's probably even eclipsed, say, Panther forebears certainly in terms of his ability to be recognized just from pictures of 'em and things like that. Like he's, I think he's more famous than Youi Newton, Bobby Seal and Eldridge Cleaver, and people like that.

yeah, I, it's hard to, it's hard to think of o other, even his contemporaries really, who match him in that regard.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, I think that's right. And it's, there's a lot of reasons for that. one of them obviously is cultural fragmentation. I think that's a huge part in that. But it's also, as you say, that his music is about telling stories in a way that is. A lot more authentic compared to especially the people who came after him.

Tupac's continued global resonance

SHEFFIELD: your connection as you mentioned earlier, that you're from Ireland and you had a particular interest in [00:06:00] Tupac as a kid growing up. tell us about that.

VAN NGUYEN: Yeah, so I, I from a school system where I think is probably stereotypical what you might expect, a Catholics, the Catholic, Irish school system to be as in like school uniforms. I went to an all boys school. Most of the schools, I think in Ireland at the time, probably still now, I'm not sure were, single sex and.

it was just, it was a very drab existence with no really extracurricular activities to speak of. So I think for us that we found and to be a, an escape or, certainly something to be interested in. For some, and for some of us gangster rap was, popular. There was another set of kids, like Kurt Cobain was the guy for them.

And like for us, I think probably above everyone else it was, Tupac. He had died by the time I got interested interested in him already. But I think that even added to the mystique around him. and yeah. And I think that there's, but you, like even, I, was just talking to last weekend actually, my, I had a friend over who's from New York and is partner for the first time.

And she had just been down in, I'm from Dublin and she had just been in Galway, which is another town that's on the other side of the country, but she was saying she'd seen a mural of Tupac there. and yeah, in the, book a little bit, I mentioned some of the murals that have popped up about him and there's just, there is something in the Irish psyche that seems to, like him.

I, had to take out some instances in the book I've just seen anecdotally that kind of shows Irish people's affinity for him. And I think again, it just speaks to that he resonates in countries with a particular history. and I, say I go into some of those, the other nations and places like Sierra Leone and the Solomon Islands in the book as well.

So, yeah, I think he was just, that was, he was just the guy for us. And in terms of probably the rapper, we most particularly, certainly some people anyway, most particularly [00:08:00] gravitate towards and certainly who, could like evoke a real sort of sense of. loyalty and, interest in maybe more so than guys like Nas and Wu-Tang Klan.

We also all listen to. But yeah, tu, Tupac just seems to, stand above all the rest.

SHEFFIELD: yeah, and I, think there's it, the, obviously the fact that he, died so young and so suddenly, that obviously it, put him to a higher status. But on the other hand, there were a lot of, guys who died young and didn't get anywhere near that iconic status.

So it's worth thinking about him. and also the other thing about Tupac, I think that makes him stand out is that because he was there, in in the beginning of the genre, and then never. a chance to sell it. who knows whether he would've or not. It's hard to say, right? But, he didn't, and, but he was able to preserve that original ethos hip hop and rap. And so talk, talk, talk about that though. Like how rap originally was as a medium.

The origins of hiphop and its commercialization

VAN NGUYEN: in, in, in the book, I, had, if I saw it as there being an opportunity to do a tangential narrative on how hip hop came from radical origins like I, I go into Tupac's Black Panther parentage and his, heritage and, hip hop was born in New York on the same streets where the Panthers, hop the newspapers and had offices and it was.

Just it was just slightly, just, a couple of years after their, the peak of their influence in New York. But it's, I think that it was still, it's from, it's like it's from the same streets. It's from the, conditions in which the Panthers sought [00:10:00] to, recruit and, sought to, provide relief for, in terms of the poverty that a lot of the people who lived in those areas were experiencing.

oh, it hip hop was a, was it was a youth movement, really no commercial interests, at all. And I think you see as, it grows, it's the commercialization of it becomes obviously incredibly intense. And I think when you think about like original hip hop, it, came, there was various, sections to, or segments to where you had, break dancing, graffiti.

These are called like the parts of the five elements that they call, they say of hip hop. But the only one I think the capitalism finds any great use for is rap music. So it becomes the dominating strand, which is why kind of rap and hip hop become, synonyms of each other really.

yeah, that's, I wanted to tell that story and I think with Tupac, he, he's, he exists within obviously the commercialization of it. he was a massive selling, he was like a massive selling artist in his own lifetime. But I think in, in, it's almost in his aftermath that some, of his contemporaries, have become among the richest people in the US and they've created this billionaire class of, rap artists.

There was almost this, race to see who could become hip hop's first official billionaire for a while. so yeah, as you say, it's, I. It would've been interesting to know how he would've, how he would've seen that.

Tupac's legacy of contradictions

VAN NGUYEN: I, I, I tend to believe that be he would've held onto to his, Panther principles in terms of the Panthers were a, Marxist Leninist movement.

he held onto a lot of those socialist principles in life, which he, spoke about in his interviews and in his songs. But, yeah, you never really know what the, indignity of aging will do to his people. But I do tend to, [00:12:00] I rather, when I consider how he would've aged, I prefer to look at his, the Panthers of his parents generation who, who never really strayed from their original principles rather than maybe some of his own contemporaries who became just, highly interested in, in, in the entertainment industry and how, kinda high, how much wealth they could accumulate from that.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. and, they didn't have a, an ideology

VAN NGUYEN: Yeah, exactly. Yeah.

SHEFFIELD: any sort, of political education on their own. it, that, that tension between capitalism the, the allure and opportunity of capitalism for people who were creating this new musical genre, it was immense.

the gravitational force of that was huge. But yet at the same time they, came from an environment in which there was really no way out for a lot of black Americans who were, they were, they went to these terrible schools. the, governments wouldn't spend more money on them, or if they did, they wouldn't provide resources out of school.

So kids were basically just stranded there in a lot of different ways. and it was an environment in which sports and, hip hop was the only way out, which is, and, a lot of times people who are, right wing racist will look at that and they'll mock it, but they don't understand that th that, that, that was the only way out like that was, if you don't have a, an education, how are you going to pull yourself up by your bootstraps?

And like that contradiction, it was something that. The Tupac, I think, much more than a lot of other rappers really did explore that a lot in, part because of his own family [00:14:00] ideology that he was brought up with.

VAN NGUYEN: Yeah. And you mentioned there, there, is these, this lasting joke. I think Dave Chappelle was one of the people who made it about, oh. Music and as you say, sports being the only, the only roots out of poverty and those jokes are, think are still made just because they seem so long lasting.

And I think when I talk about the, how, hip hop becomes consumed by, capitalism. One thing I say about it is it's more so than nearly any other art form. It does capture as well the, crush of capitalism. it, it gives, I. It's probably the clear, it's consistently given the clearest dispatches of what it is to, exist in the, at the bottom of the capitalist system.

And, and to be at the, say, the bottom of the sharp end of it. But I, two, I think one is, one thing is that most wrappers rappers be when they, when, trying to solve, trying to achieve upward mobility through capitalism, they, that it become, that's a core theme of rap music.

And very few, certainly in the mainstream have ever put forward socialist ideas within their music or, esp like socialist principles or a socialist perspective to say that the system isn't, is set up. That it's always going to have this kind of class at the bottom who are, struggling.

there are some like rap rappers like Paris and, a no name, but I think of the one, obviously the, one to every esp any sort of sost principles in his music and in his interviews that became clearly the most famous was Tupac. And I think that he, obviously, he inherited those from his mother. And, and yeah, and like he, unlike, most, he was, very, I mean he, hated wealth inequality as one of the real that people always talk about the duality of Tupac or the contradictions of his, music and how he [00:16:00] could, put forward one set of ideas and then maybe contradict himself within, a couple of tracks later.

But if you look at. That is hatred. He had a wealth inequality. it's one of the real consistencies of his life. And he always maintained that it wasn't right for the rich to have so much and the poor, to have so little. yeah, and I'd say it would've been, it would've been interesting to that he hopefully would've, he would've kept those had he had, he died.

But I tend to believe he, he would, like even he was planning his own company around the time of his death, but within that he had like plans for like, school programs. And I think he wanted to have a kinda, an egalitarian slant to it. so yeah, was, very in tuned with that, side of America, I think.

And that's who he saw. I think as his base, as his people, like his, he saw the people at, the bottom of the capitalist crush being, those, he, most wanted to reach and speak to.

SHEFFIELD: yeah. and also yeah, and I'm glad you mentioned that. I was actually gonna bring that up. yeah. and I guess, in some ways, you, mentioned No Name, like she's in, some ways trying to do some of that herself actually with community centers that she is. Involved with in trying to help get started? do is that a thing you followed at all? not

VAN NGUYEN: Yeah, like I've generally followed her career and I know for example, it's very interesting, which I think she passed on doing a song for the and the Black Messiah because she saw as downplaying the actual ideology of the Panthers. And I think that is actually a, it's funny because the Panthers are the most lasting from that era of, revolutionaries.

I think they're the best remembered more so than say, the Weather [00:18:00] underground or the Black Liberation Army that came in their wake. But they, their ideology tends to be very reduced to the lowest terms as people just consider them. Like a group who were only interested in, killing Whitey.

But like that they were, I say they were Marxist Leninist. They didn't see white people as such as their oppressors. They saw the capitalist class, their oppressors, and they would've included the black capitalist class within that. that's why they were able to ally with groups like the Weather Underground, who were all majority white, if not all white.

That's what like, they were encouraged the White Panther Party in, Ann Arbor to, establish itself. And that was another thing.

The Black Panthers' influence on Tupac's mother

VAN NGUYEN: I think I, I found an opportunity to do with the book because if I was gonna do a political history, it was obviously important that I chart it his mother's life that.

Who would, that, who ultimately both influenced his, ideology, but I think gave his, icon a sense of historic continuity where even if you have very limited knowledge of Tupac's life, that he came Black Panthers. So I really wanted to actually show readers who, the Panthers were and how there was more to them than, the fists in the air.

And they were actually this intellectual movement and were, yeah, they like Huey Newton, I think was a, a very trenchant political thinker and writer. and yeah, a lot of that tends, to get forgotten.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, it does. And, the other thing about them, I think that is. Different from, let's say, today's radical left traditions by and large, or at least ones with popular audience. like a lot of the popular leftist content creators of today, they don't, actually build anything. A lot of these modern day leftist personalities or number one, they don't write anything. They just talk on YouTube, [00:20:00] primarily. then number two is that don't build anything. So where, and that's a huge contrast with what. The Panthers were doing to try to create a lot of different local groups, chapters and, things like that.

And within, the book also, you talk about some of the connections that they had within the, with the, Irish Republican army and some of the people who were trying to fight against the, British, domination and, subjugation of Ireland. You wanna talk about that?

VAN NGUYEN: Sure. yeah, just, to pick up on your first point there. And I, think that's why the Panthers were seen as such a threat, in the minds of j Edgar Hoover and, other people in power, because not only did they. Voice socialist principles, but they put them into action, right? They set up the school breakfast program, which was, it was a free to the community where parents could bring their children to make sure that they had a decent breakfast before they went to school.

Because, I'm sure every study has shown this, if not, before. Then since that children who, if who aren't hungry are obviously going to more, able to perform in, classrooms. they put on like a free ambulance service for, their communities. Yeah. Like, it's what, it's still such a big issue in the US in terms of he healthcare that's affordable and, accessible.

And so they were putting in real time programs that actually helped people, in a very real and tangible way. And I think that's what scared the establishment so much that they did, Viciously go out and to crush them in, this kind of very deliberate, clandestine way.

And, unfortunately, I don't think any group could have stood up the, tyranny that was, put on them by Hoover and others. but yeah. You, mentioned they did. Yeah. They had, they, I say they had links to. They were in [00:22:00] solidarity with movements all around the world who they saw as, in, in league with theirs.

And, they had the Irish Republican movement in Ireland was, one of them. And there's, always been these between Irish freedom fighters and, like Black American freedom fighters as well. So it, that's just the one, example of, how they come together and like the Irish Civil Rights Movement the, sixties, it, took a lot of its cues from, the Civil Rights movement in, the US as well.

And I think that's what I was getting at earlier in terms of, there's something in the Irish psyche, I think that. That Tupac appeals to, and the fact that I think he died violently is part of that. Because that's something that happened to all of Ireland's revolutionary leaders. the leaders of 1916 rising.

they all were, they're all killed violently. so yeah, I think that's why you see him turn up in, in murals and and memes like through meme culture guy, like Irish kids have been trying like solidifying those kind of bonds as well between two PAC and Ireland.

So, yeah, it was, I think it was, in that tradition and for me, I suppose as an, Irish person, that's why it was why I wanted to make it part of the prologue of the book just to declare my, my my, my kind of status within, the, within as a person con considering Tupac and, Yeah, I think it was, made me feel that I was well placed to talk about him as, a global icon. As as, much as I, as a man.

Masculinity and gender within hiphop

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. and, one of the other, I think, reasons why hip hop as a genre, besides the fact that it was very innovative and different, [00:24:00] from, the other musical forms that had preceded it, that was made it appealing to a lot of people was that that it, ex early hip hop really did explore a lot of themes of, what it meant to be a man. In a way that other genres really even now, still don't do. and it's, significant because that those topics, really are politically extremely relevant now. And, and I think that's part of what gives early hip hop, especially Tupac, a lot of the continued relevance was this tension between, not wanting to be controlled or dominated, but also as, Tupac was trying it. And, talk about his contradictions after this, but, like his aspirational idea of saying that, look, yes, I want to be in control of myself and set my own destiny, but I understand that, I'm part of a community and that I'm not gonna be just a nihilist out for money.

VAN NGUYEN: Yeah. as I say, I think that he saw himself as, in league with the go, the global proletariat. And, that was, I think he said specifically in, in an interview like, as long as I had, it doesn't matter about the authorities. this was, he was at the time experiencing a lot different court cases.

I think he says, as long as I have the, hearts and the minds of the people, then, I'm always going to be. Important or relevant or, I'm not quite, I'm, paraphrasing. I'm not quite sure what word he used there, but that was his, that was, I think, a part of his outlook. And again, I think it just came from his, mother's generation.

And, it's the off reference and off, spoken slogan of power to the people, he, came from that stock. So yeah. and I think that it's one of the things that, [00:26:00] that sets him apart. It's certainly from his contemporaries. And yeah, I think that what's, interesting as well towards the end of his life, because undeniably like, when you look at like his all eyes on the album, it's, it moves away from the earlier socially conscious stuff that he made of his, the, more famous socially conscious music like Brenda's got a baby and, Keep your head up and stuff like that.

There are, those are earlier songs. He, definitely moved towards this more like Hollywood blockbuster gangster rap. Sound, but when you get to Machiavelli, which is the last album he completed in his life, it, it was released after he died. But, it was his, he, finished the album. So it was his, vision of it.

much more, I think, returning to his roots where he very specifically shouts out people. Some of his mother, Afeni, Shakur's comrades, people like Seko Odinga Jamal Joseph Matula Shakur, I think he mentions as well. yeah, he, I think he, he died while, interested in, reigniting those, values that he always had when, but as we'd say, he, was very malleable.

And I think he had a sometimes to, often I'd say to his detriment, this tendency to this kind of chameleon tendency to absorb the people that were around him. And often he wasn't surrounded with the best people. most famously I would say that Suge Knight was probably not for Tupac. The man, he was not the, best figure to be in his life at the time.

Obviously for Tupac, the artist, it proved that during his period on death row, he created some of his best music. But but yeah, I think, but then like when we, talk about him as, an icon as well, like the, I think it's the, it, is those contradictions that malleability that appeals to people how he can, he serves so many different roles for [00:28:00] different people.

And if you talk rebel Soldiers who've fought in, places like Sierra Leone, I like one of, I think one of the things that they identify with was. Some, it was, the fact that he was seen as being able to look after himself, that he was, a lot of these, like we're talking about the child soldiers of Sierra Leone who really embraced him.

A lot of them had been in jail and they, that was one of the reasons that they identified Tupac as well. So he had been in jail. So I think it, it is, it's like this kind of perfect recipe, that this symbol came to be. And with the book, I, think one of the things I did want to do is, not only discover of how that came to be, but also to, to, delve into the man too and, just and like the Panthers, as we were saying, he, I think the further we would get away from Tupac's death, the more, the fear is that his, that he can become just his, the symbol can start to overwhelm the man.

And he his icon can be, as flat as, the posters that people of him hang on the wall. so yeah, that was also part of the, I think the, appeal to me of, to do a project like this.

Gender and sexuality in the Black Panther Party

SHEFFIELD: On the question of masculinity and hip hop culture, and especially for Tupac, as you note in the book that for the Black Panthers. It, there was, Newton. He was, very known as somebody who was hyper masculine. But later in his life he a lot of what he had been inculcated to believe about all of that stuff, and actually became a supporter of, gay liberation and made that a pretty big focus for, the Black Panthers.

That's something that I think that, lost in the, historical mist, and you bring that out a bit.

VAN NGUYEN: it, goes to what I was saying, I think about the Panthers being and, being, simplified. But one of the things that does [00:30:00] is forgotten is that a huge amount of the rank and file members were women. And it was made clear in Panther doctrine that women were not there to service the Revolutionary men.

They were there as comrades in arms, which was, I think, a real departure from the, ideology of Newton's and Seal's Hero, Malcolm X, who was relatively socially conservative on, women. so, that was quite at the time. Now, what's I think interesting as well is that while All Panther men, I think, would've signed up for that and they would've.

Believed in it. For the most part. it's very, it is still, it's difficult for men to completely shed themselves of the misogyny that they've been raised in. And I'm not just talking about that era of, men in America. I'm talking about to this day, and I'm talking about myself in that as well.

Whereas you're as, a man, I, was raised a society which is inherently, misogynistic. So once you reckon with that, it's, I think it's a lifelong process to, to rid yourself of those impulses and those, ideas as much as as much as you wish to. it's still, a process.

So I think the pan, the male Panthers at the time were probably going through that. And so the women had, it really was a struggle within a struggle for them in terms of they were part of the greater liberation movement for, black people in America. But they were also within a, kind of a movement as well.

It. Being seen as, equals to the, men in the party. And I think they were, among the, I say 'cause they were made up so much of the rank of file, they, took on a huge proportion of, things like the, breakfast clubs, the Children's Respect Club, but also, and about in the book, like Afeni Shakur, they were also [00:32:00] willing to be there for some of the more difficult moments.

And by Afeni Shakur herself told a story in, about how she w was willing to be take part in, in an armed robbery, which is been my theorized by some of the journalists that the Panthers would sometimes do appropriations, these, yeah, these missions of appropriation to help fund them.

And she wanted to be a part of that. So she, wasn't going to shy away from that element of being a revolutionary either. yeah, I think it was, yeah. Good. It was a good moment. It was a good opportunity in the book for me to talk about that, element of the Panther history and, the progress, the progressive nature of the Panthers in terms of gender ideology or gender equality rather. And, also difficulty it was in putting it into practice and how it, it, wasn't executed perfectly.

SHEFFIELD: Just. Going back to the idea of gay liberation within the Black Panther Party that, you know, the fact that many of the member, or some of the most prominent members, or the inner circle of the members were women who were bisexual or lesbian, also provided a direct way of, Newton, as you note in the Book of Newton, realizing that, he needed to reconsider this.

And, that was something that was a big, huge departure from Malcolm X and lot of the other, black leftist or left wing leaders more broadly irrespective of race at that, especially at that time.

VAN NGUYEN: yeah. like Newton wanted gender equality as part of the Panther ethos. He was also a big supporter of the Gay Liberation Movement at that time. and, he, Wrote openly about how, similarly to, like, how I was saying, how men need to confront the kind of, the mis the misogyny that's been ingrained in them through society and through, their upbringings.

Newton was open that about him having to attack and confront the [00:34:00] homophobia that he had previously and the homophobia attitudes that he was raised, to, experience. So, yeah, again, that was, a quite progressive element of the Panthers at that time.

And, again, it's just part of, I think about how Newton and the Panthers general just saw themselves in comrade ship with all the, liberation movements around the world. And, for them, gay liberation and black liberation weren't to be decouples. They were one and the same.

SHEFFIELD: yeah. And, you you have that, as, that's the title of the book is Notes for my Comrades. that's it's, I think that a lot of people who might have more leftist economic viewpoints, there's a, they, there's a temptation for a lot of them to think, we can't, we should never focus on any of these other identity politics issues because we should just focus on the economy and people's needs with that. But that's really not what the people who, you know, who they purport to admire were going forward. Like they were trying to do the full spectrum and, be there for all the comrades as, you were saying.

VAN NGUYEN: Definitely, and the title it comes directly from a, Tupac lyric. But it's from that last album, Machiavelli, I was talking about, from a a song called Blasphemy. But again, I think it, the lyric itself spoke to that period of his life, Tupac was wanting to reengage with those roots.

And he said, I, have words from my comrades, I think that he was speaking not just to that era of, activists who I, mentioned earlier, he actually names drops, say the global, the global proletariat who he saw himself as is as one of, and, in comradeship with.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah.

Obama and Trump in hip hop culture

SHEFFIELD: and, I mean there's, two people I think that [00:36:00] perhaps could be. Regarded as at least at one point in their lives, as similarly iconic. And, but they're not musical people, and that is, Barack Obama and Donald Trump. both of them became universally recognizable. And, it's notable that they both also played a, a and obviously Tupac wasn't really talking about either one of them.

But on the other hand, they, I think they both represent some sense this these kind of dual or the conflicts that existed hip hop, even in its earliest days.

And you talk about, Obama in that context as a, the first black president, but also Donald Trump, as a, I think maybe a lot of people have forgotten, but the, as you talk about in the book that, Trump, in the mid, early to mid two thousands, he was, name checked quite a bit and got a lot of respect and, which, doesn't red down well to the people who were giving it.

VAN NGUYEN: Yeah, it's, funny because Obama has sometimes been referenced as the first hip hop president which I, it doesn't make a whole lot of sense to me. Although, but Trump, he was actually in the nineties, he was regularly name dropped songs. In rap songs because he was seen as this, figure of big business and of, business ingenuity and of flashiness.

So like he even, I think he appears on a Method Man album as a, skit as well. So he was happy to embrace that. And he was, he was a New Yorker, obviously, which was from the birthplace of hip hop too. he was pretty much well liked in, I think in hip hop circles before he entered politics, except the one person who called him out was Tupac in an interview, not so much Trump the man, but he called out just the [00:38:00] idea of the, a mega, the mega rich, to hit to Tupac. Trump symbolized everything that was wrong with the way wealth is distributed in the us. say, how can a private individual own planes when parents can't provide.

Meals for their children in the same country. so yeah. And so it's, funny to me as well, that Tupac is right there as well. I almost if the birth of, I would say, which is, I dunno if this is simplified and some, it's not my, this is not an original idea of mine, but I, do find it quite, appealing and quite neat that it's often said that Trump decided he wa he wanted to run, be president when Obama mocked him during that speech, And one of the things that I think Obama was poking fun at him was he was. he was going to return to being, to, to being this kind of conspiracy theorist. And one of the things he said was like, who shot Biggie in Tupac? So it's just funny that Tupac's name was mentioned during what is sometimes considered the genesis of Trump.

The, person, or sorry, Trump the politician.

Former Panthers still have hope for the future despite Trump

VAN NGUYEN: I think in initially Trumpism wasn't as big of a concern in the book, but then the. The reelection happened. which was actually quite near the end of when I was finished finishing, but it became a little bit more pertinent.

But I, one of the things I, think I wanted to get across in it was how I noticed that upon the second election that Amer American progressives and the Democrats and anyone really, left of that there was this desperation, this, defeatist nature where it was very different to the feeling of when he was elected the first time, when it was very much okay, the resistance starts now.

And it was just like everyone was, you had this, all these tech billionaires just lining up to just, worship them and, to just, bend the knee and declare [00:40:00] their loyalty and the way, which is, it's actually, it's good to see that recently of things like the No Kings, protests have been more encouraging.

But I, wanted, I think to get across in the book that panther, the generation of Panthers who I had been talking to and, telling their story. I, they, I had most that generation, like sixties and seventies revolutionaries. I had asked them some sort of variation of the question like, are you, do you still think the revolution is coming?

And they all, they like to a man, they all said to a man to and to a woman, they all said yes. And I, I dunno if they are like just really, optimistic or they wouldn't admit, want to admit not being, but was I think, heartening to see that even they who've lived from everything from, as I say, be suffering from at the hands of the, of their own government true now to this dangerous new reactionary form of politics in the form of Trumpism.

That they maintain their belief and they've never strayed from the. Their kind of core values and they, I think they book that trend or that idea that, the older you get, the more pragma, the more, pragmatism you start to show and the more to the center you kind of drift, but they've never given up hope.

And I, if there's one hopefully lesson in there, maybe for some people in the book, it's that, not to, stop believing.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. and and this ha happened after the book was already, in print.

Trump's 2024 campaign reached out heavily to hiphop performers

SHEFFIELD: But is the case that leading up to the 2024 election, you did have several different rappers come out in favor of Donald Trump. And, now one of them, rolled it back later.

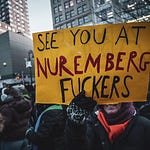

So Sexy red was infamous for, supporting Trump for a while. And then she rolled it back once, the, once Roe versus Wade was overturned. there, there were, Lil Wayne went and with, PO [00:42:00] posted a picture with Trump and even Snoop Dogg said, he had no problem with Trump. So there, there, is something, like the, Trump people. They very clearly were trying to become, le to, leverage a lot of these hip hop legends to improve his standing among black Americans, and in fact, all of the most reliable pulling analysts. pulling analyses have showed that Trump did in fact increase his percentage pretty, significantly among both black women and black men, and also Hispanic men as well. depending on the poll you look at, he got the majority of Hispanic men to vote for him. So there's, and, and you talk about in the book, the, about the film Scarface and how central it became to a lot of, hip hop iconography and lyrics. They, the Trump people also tried to do that with his mugshot, like they tried to, make him into a Chi Guevara type figure. and I think that's one of the most perverse and awful things that, they've essentially tried to turn Donald Trump into Tupac. I think that's actually what they've done.

And for a lot of people. They really do see that. Like they actually think of Trump as the inheritor of Tupac, which I know it sounds absurd delusional to you, probably, but I think that's the reality that a lot of people are looking at.

VAN NGUYEN: like I, I, Did see online somebody Photoshopping a maga hat onto Tupac, and I think I said that I have the cure for that with this book. But, yeah, like I, I think it did irritate me when I saw, the photograph of trumpet, his fist in the air and, the, kind of the [00:44:00] maga movement seizing on it.

Because like for me, or I think the fist in the air is not for people like Trump. It's for the, it's for the left, it's for the proletariat, it's for the revolutionaries who, who fight for equality and justice from the left. So that was irritating to me. But I think you're right as well about it's funny how the, some of the rappers have started to snap into line because in, in the book I did mention how, I can't remember the wording I used, but it was basically how any, no.

After being generally embracing of Trump in the nineties, once, his first presidential run kicked off and. And that he started attacking, Mexican Americans and people like that. he became persona non grata amongst rappers. But I think since I finished the, book, I have started to notice, yeah, there's, there is this reversal now, or it's not quite a reversal maybe, but as you say, like they, they're starting to one by one fall into line a little bit.

And again, I think it's just part of this just desperation. And I wish I get, it's, hard, it's easier for the psyche sometimes to, accept it or to try to convince yourself that, Trumpism isn't inherently, a, fascist right wing, reactionary movement.

And to try and, try to see it as being somewhat normal just so you can live your life. But, but yes, say it's, encouraging to see at least as some of The, the pushback to, the ICE raids and things like that that are going on.

And I think that in, hopefully in the, there's, in the book there's maybe lessons for the modern left in, terms of of learning about the history of movement of the, of radical leftist groups movements the importance of solidarity [00:46:00] and the importance. and I think the, idea as well that, no revolutionary actions or protests or any sort of, movement or any sort of activism is worth doing.

And it's never wasted, no matter how desperate the situation currently feels.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah.

'Coolness' as a non-political voter persuasion method

SHEFFIELD: and it's interesting, there was a study that just came out on this point that, I, think that a lot of Trump opponents, they really haven't figured out he has cultural cache and, that is why many people support him, and they don't even know what his PO policy positions are. And so so there's a study that just came out, the New York Times has a piece on that they we're recording this, said that they, that was a study across different regions of the world, 12 different countries. And, they asked people, what is, what does cool mean? And there was almost remarkable unity.

And, it was the attributes that a cool person is said to have is that they're extroverted, they're hedonistic powerful, adventurous, open and autonomous. And that's pretty much the image that Donald Trump projects of himself. And, obviously he has a lot of other that make him repel it and, authoritarian to people who actually know what he's about. if you don't know what you know his positions are or the things that he's done, just see those images and and for people who wanna oppose him effectively, you've gotta get into the culture and, project something in a similar way if you, wanna stop this movement, I think.

VAN NGUYEN: yeah. And that's, that seems like a bizarre actually definition cool. but yeah. Yeah. He's, [00:48:00] he, it's say it's been, he, it's strange now to see as well that did see the democrats who've seemed to have settled on the idea of defeating MAGA is to almost be MAGA light and I am, again, it's encouraging to see the recent election there in New York or the, mayoral sorry. and but to see that there that charismatic politician can come through with good ideas that appeal to people, and it's always, it's, something that Penny just never seems to drop sometimes with Democrats that it's actually policy that, that is going, that winds over, is going to win over voters and, ensuring that your policies are gonna work for, working class people or for people who are

SHEFFIELD: But you gotta do it in a way that people will find entertaining and can break through all the noise of their

VAN NGUYEN: Yeah. And the, pageantry of politics as well. which is a whole other, sphere. but, yeah, and I say I think that with The, the book in particular, and it was for me, a this ability, I think, to tell this kind of 50, 60 year history of, American radical politics and resistance and activism.

So it, it goes up to the, the Black Lives Matter movement and how they have hugged Tupac's icon so closely. And he's almost I think this perfect through point because like you think of a song like Changes, which became a real Black Lives Matter anthem. And he specifically, invokes the name of Huey Newton in that so it's like a song that was recorded in the nineties that drew inspiration from the radicals of the sixties and then becomes an anthem in the 2010s, 2020s.

so yeah, [00:50:00] he, I think that was one of the, things of the book was to try to, Was to, bring it into the contemporary and to, and the, modern political temperature, or sorry, climate that the US finds itself in, which is, easy, so volatile. It's changed even so much, even since I, finished the bulk of the book.

How Van Nguyen brought oral history into the book

SHEFFIELD: And in terms of, so your technique with the book here, like You I, the other thing that's, that I, think is really notable is that you are telling the, you talk to a lot of the people who were personally involved, and these are people that. journalist, as far as I can tell, really talks to them all that much.

except for, in kind of a superficial way. But you were actually talking to them about, about their ideas and what they thought about things other than, oh, tell me what was he like as a kid? What was his favorite, ice creamer, whatever. And that's, that's the kind of important entertainment journalism that I think we need so much more of rather than just this bullshit sucking up to people. That's what is the difference between art and entertainment, I would say, is that, the lyrics actually mean something. They weren't written by a committee and they tell a story about shit that matters.

VAN NGUYEN: I, I think one, one of the things that was, important to me to do with the book was even though it's a political history and as I mentioned it, it's this 50, 60 year history of, radical American politics, but it's also a biography of Tupac. if you don't know much about his life, you should come away with a good knowledge of the story.

But I wanted to do whatever I could to differentiate it from other tellings of the story. And I was willing to, I did dozens of interviews for it, but I was willing to talk to anyone, but I was particularly to keen to talk to people whose stories hadn't been heard as much. So rather, if you watch documentaries on Tupac, you'll often see some of the same faces.

which was cool. And I, talked to [00:52:00] some, people who talk about it regularly as well, but I found that, yeah, some of the best sources were people you actually don't. Don't speak to or don't speak on him as much as maybe others. And I say talking to the, radicals of the sixties and seventies was very, re rewarding.

And I think they, I was really honored of how candid they were with me and, yeah, it was, I it was yeah, just, tr trying to be, I think it was not a lot of traditional just muck wreaking journalism in it as well of kicking over stones and seeing who I could find that was adjacent to this story.

and even like things that I completely, I didn't expect for. So for example, I visited the, spot where Tupac was shot in Vegas. And, I was talking to the taxi driver who was taking me down and He had actually been working that night. He was, I think he was a waiter at the time, and he was driving to his shift and he passed the scene of the shooting.

And he, was telling me how he noticed it was unusual that there was only one detective car there, but he started repeating then all these stories or all these theories probably some of them unsubstantiated. But when you, talk to someone who's been in Vegas for so long like that and you, really learn that Tupac has become part of Vegas lore now.

he's, almost, he's you think about the icon iconography of, Vegas, you think ex people like Elvis and Sinatra and stuff and is there with them now I think as well on the basis that was, there and just, yeah, as he's speaking to a text driver, which was completely unplanned and you realize again, just the.

The size of the man's meaning, and, his importance that he just, he evokes these, the, these, sentiments and these, conversations that do happen around them at all, all the time. [00:54:00] So, yeah, it was, the research was definitely very, of the more rewarding aspects of it.

And it's, it was, it's it's a really interesting story as well, just as a writer to, to get into with interesting characters. like Suge Knight and, like people like Matula Shakur, who was his, stepfather who's a kinda a character in the book to, get into them.

So yeah, it was, I say ultimately very rewarding of a project to, to undertake.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. and speaking of should Knight, he's been vocal lately in the media. He's resurfaced as a commentator on the trial of, Sean Puffy Combs. And I, I, think, Combs is, really a, the perfect example of just how corrupted hip hop later became.

And obviously we're seeing a lot of that in the trial with his, and criminality, but all of that was on display. who he was as a person I thought was always visible. Well before the trial, this guy, was a, is a piece of shit. And anybody could see that. and but, anyway, so Suge Knight's come out and trying to, he's calling on other of the, of his contemporaries from, the early days of the nineties and telling people to come out and he's saying, look, they're not, they're not doing it.

Because they're afraid of not, they're not afraid that they'll get hurt, but they're afraid that it might compromise their, wallets.

VAN NGUYEN: Yeah, and I think it's because it's probably easy to forget now that, Suge Knight was probably the epitome of, the guy who saw hip hop as being its ability to achieve it, mobility and up to the, real 1% class through the entertainment industry. And as much is [00:56:00] critical of the entertainment, like the kind of the capitalist nature of it.

Which I am, it's, I suppose it, it is, it's, you have to acknowledge as well that this. Era of, label owners of hip hop label owners. They were motivated as well to not be like the, guys like not for the industry to, to, change from the era of the sixties and, earlier when black talents did not get the enough of the pie that they deserved and that it, they weren't part of the class of like CEOs and, owners.

so like that they were motivated by that as well. I think so. But yeah, sugar Knight was, certainly one of those guys and, but unfortunately his, for him, his, I think his, nature of his business practices ended up getting the better of him. And like he, he was, he was unable to transition into a person like Jay-Z who became obviously a highly mainstream figure, but.

Yeah, I'm not even sure. I think like with, I think with Jay-Z and it's, sometimes it's, easy to forget that he was part of Tupac's, he was a contemporary of Tupac, because he seems so much more of the 21st century. But, I think that with people like him and obviously Dr.

Dre, who, was obviously famously collaborator of Tupac I think I, I think for them probably those East Coast, west Coast Wars wa when Tupac and Biggie were killed was probably a, moment for them when they realized like, okay, we've, this has been good. Like the East Coast, west Good Wars was good for business there for a while, but we can't keep doing this.

Like we can't, we just lost two of our most talented artists. if we keep going, this is just unsustainable. And I think that's when really in, in the wake of Tupac and Big's death, you do see that, that. [00:58:00] That That kind of as I, called them earlier, like this, billionaire class of hip hop mogul starts to, really develop.

and they were a couple of the guys who were really savvy and, able to, take advantage of that.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah.

Eazy-E's legacy in hip hop

SHEFFIELD: and one figure who I think also was enormously influenced. Mitchell in the early days that died very young as well. but not from gun violence was the Eazy-E And, he I, think in, I, he, you could say perhaps that, oh, he got sour grapes 'cause he got left out. But in some sense I think he did see where things were going. And, he talked about it in, in some of his, in his final work. you wanted to talk about ECE in, in, this context.

VAN NGUYEN: Yeah, I say he was one of the guys who's probably well poised to, to become more powerful than He was even in what we consider like now, his heyday and, he's, obviously a very important figure in, the history of, hip hop. And again, he was another interesting character in the book.

Book. He's not super central to the plot or anything, but it's, he, when you, look at that era and say there's these, all these stories of how, Suge Knight managed to get Dr. Dre out of his contract. And it's, all it's, all so dramatic and there's almost like a Shakespearean aspect to it, I think. But yeah, unfortunately, yeah, the Eazy-E was certainly one of the, real tragedies of hip hop to, to have lost him when, he was lost. he was a very, very, a very shrewd man, like a very savvy business operator. And I actually think that. Probably one of the, lasting influences he had on that, [01:00:00] on, on, Tupac and at least that generation was, it was easy.

Who really popularized, I dunno if he, was the first one to say it, but I think he probably popularized it more than anyone was the idea of the, studio gangster, he called him. So this was during, when he was beefing with Dr. Dre and he dubbed Dre, a studio gangster just to call out his, actual credentials.

And I think that really establishes this idea that if you wanna be a gangster rapper, your connections and your actions and, your, ethos and your life has to be legit. or else you're just like this fake. And that's. Probably a powerful thing to happened to Tupac or that Tupac heard, because Tupac was he was, he came from art school, like he was an actor.

him, I think playing the role of, a gangster would've been no problem. And in the way we've probably seen guys like, Rick Ross do in the years after more shamelessly. But that wasn't the temperature of the mid nineties in, hip hop. And that, easy was one of the ones who set that temperature.

And people liked Tupac, of course felt that they had to, had to be consumed by the culture. And I, Tupac wasn't from la he moved to LA during the, real height of when, Crips and Bloods were really s. Becoming known all across the world as exemplifying gang culture and gang violence.

And said earlier, he was, he had this chameleon quality to him where he tended to absorb the characteristics of those around him. So think we're talking about easy in relation to this story that's probably in indirectly one of the real lasting legacies he had on the Tupac story. And really the story of the east coast, west coast wars and gangster rap in general where yeah, you, if you wanted to be a part of it, you, actually had to be legit or else they were gonna call you out as, some sort of fake,

The meaning of 'thug life'

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, and I guess, to that end let's, there, [01:02:00] the, slogan or I guess the phrase that, that was very associated with Tupac the term thug life. it's, I think nowadays, at this long juncture, far removed, a lot of people have no idea that was actually an acronym. and that he was trying to have it mean something else than just what it meant on the surface. And I, there's a little bit of an echo perhaps in the slogan of Black Lives Matter. I think in that, it's a, it has a surface meaning, which is not correct. and so it, if you, but you have to know the context.

And if you don't know the context, then the meaning is laws. Can you talk about that?

VAN NGUYEN: Yeah, I think it feeds into what I was saying earlier about. Tupac being his what? icon being somewhat flattened. And I think that thug life is, a real part of that, where it's, he's obviously very associated with the, that expression. If you look at t-shirts, like so many Tupac t-shirts would have thug life written on them.

But it, I think that it's become a very surface level idea just in terms of you live your life by what I guess we would consider to be thuggish, Or like you see those that internet mean that was happening for a while where someone would say something silly, confrontational.

And the, a lot of the gangster rap music plays and tug life appears on the screen and these sunglasses appear on them and stuff like that. And I think that just exemplifies how, surface level has become. But Thug Life's a Tupac. I had a few different meanings, but one of its. Of its meanings.

It was a manifesto that he developed I believe with his, stepbrother rem and his stepfather Matco and maybe Jamal Joseph as well. It's, some of the reports are a bit murky, but he, it was a, it was what he considered like a code of conduct for LA's gangs. So [01:04:00] I think at the time when, I think the, gang culture around South Central LA in particular was really eroding the social fabric for everyone.

He saw this, code of conduct that he is written as something to alleviate that, those problems. And it, was, I think it was really heavily based on, in, in a, like a real politic where it was. Things like, it, it wasn't advocating the complete putting down of guns. 'cause I think Tupac probably acknowledged that wasn't gonna happen.

But if you felt, if you, if you put a set of morals on it or a set of rules, it could alleviate some of the, worst aspects of it. and I put it together in, the book with the, Watts truce, which was a pro, which was probably a much more effective movement in terms of reducing the amount of gang violence because it was more effective because it was developed by former gang members who a lot more cachet in the area than Tupac was a bit of an outsider.

But I think just by reading it and just by his, desires it, to, to, develop this code of conduct, I think it shows some something of his ideology at that time. And and yeah, I think he. He, evolved then he used it as a bit of a catchall term too. And I think that there was a bit of, I think, retaking back that word tug.

And it's if you're going to continuously call me a tug, I'm gonna embrace that term and I'm going, I'm gonna change it. I'm gonna, it in the way I want to interpret it. So, yeah, I think if you're looking at that period of his life, kind of 92 ish, I think it really signifies his, thought process at that time.

And that's why it was, I guess I couldn't really do a political history of the book without really trying to unpack what tug life meant. And again, just, for hopefully the purposes of maybe alleviating the, fact that it's become, if, not misunderstood, then certainly reduced to the lowest terms.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, [01:06:00] there's just a lot of, good stuff in the book here. I encourage everybody to check it out. people who want to keep up with you, Dean, what's your, recommendations for that.

VAN NGUYEN: like I'm on all the, most of the, social medias you get on Instagram. I am, I do still have a Twitter account. I don't really, I'm trying not to use it less. I'm, I, like Blue Sky. It's, that's, I've migrated a little bit more over there. yeah, I'm still on Facebook, yeah, you can reach out to me on, those platforms and, and yeah, that's, probably the best.

SHEFFIELD: Okay, cool. All right. thanks for being here, Dean.

VAN NGUYEN: Thank you the interesting conversation.