Why Trump won: Democrats have a coalition, Republicans have an ecosystem

Americans preferred the vice president’s policies, but her campaign messaging was overwhelmed by a titanic far-right ecosystem that the center-to-left refused to counteract

This essay is the ninth in a series called “How This Happened,” examining larger trends in recent American political history and how they manifest in today’s politics. Please subscribe to receive future installments.

It’s not official, but it’s obvious by now that Donald Trump is going to return to the White House next January. It’s easy to blame the voters when your candidate loses, and I can understand the impulse. But the entire point of democracy is that the people have the right to vote for whomever they wish. Ultimately, if citizens make the wrong choice, the responsibility rests upon the leaders of the losing party.

From a tactical perspective, Kamala Harris did quite well as a candidate. She won the single debate that Trump had with her. The Democratic grassroots was historically enthusiastic about voting. The crew behind @KamalaHQ was incredible. She raised a record amount of money for a presidential candidate. Her campaign had an incredible ground game operation. But it wasn’t enough because tactics are not strategy.

Despite their fantastic tactical abilities, the Democratic Party’s top leaders have been outmatched and outclassed strategically for over 40 years by their Republican counterparts. Most Americans completely disagree with the Christian supremacist movement that dominates the Republican party. Only 29 percent of the public, according to the Public Religion Research Institute, have viewpoints that could be described as “Christian nationalist,” but this small minority just convinced tens of millions of other people to vote for their hand-picked candidate and his down-ticket allies. MAGA did not win the election for Trump, it was people outside of it.

As the returns started looking grimmer last night, I feared that the election was going to be decided by the people who didn’t like the candidates. Now that we have the final exit poll data, it looks like that is exactly what happened.

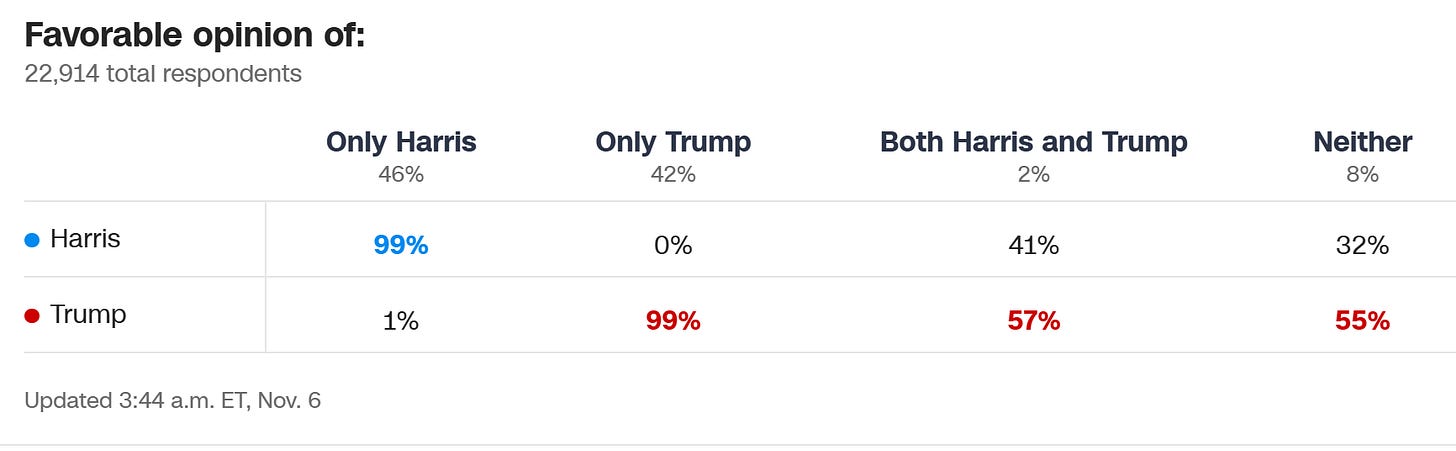

According to the survey, both candidates did exactly the same among people who liked them, 99 percent of voters who liked Trump voted for him, ditto for Harris.

The election was decided by people who disliked both candidates. As you can see in the data table below, 8 percent of Americans surveyed disliked Harris and Trump. But they clearly disliked Harris more since 55 percent voted for Trump. Only 32 percent voted for Harris.

(A similar dynamic prevailed among the 2 percent of voters who said they liked both parties’ nominees. 57 percent voted for Trump.)

Media platforms vs. policy platforms

Throughout his political career, Trump has always bet on getting people to vote for him who didn’t like him based on what political scientists call “negative partisanship,” people basing their vote on opposing an undesired candidate instead of supporting a favored one.

In 2016, Trump’s primary message was how he would give far-right Christians the Supreme Court of their dreams, and that Hillary Clinton was concealing a fatal disease diagnosis. In 2024, Trump’s closing message drumbeat was fearmongering against transgender people.

Objectively, it’s absurd to think that trans women are going to take over women’s sports. There are almost zero trans athletes in America, which is the reason you always hear about the same handful of people in Republican messaging.

Likewise, the notion that millions of cisgender men would copy Trump by walking into women’s locker rooms is ridiculous. It is already illegal for males to enter female-only spaces, and laws allowing trans people to use the bathroom fitting their gender identity offer zero legal protections to lewd cisgender people.

It wasn’t just Trump’s closing message that was ludicrously false, either. He relentlessly pushed the lie that America’s economy is in a terrible state, despite the fact that the inflation rate and unemployment are low, and GDP growth has been consistently positive.

Trump’s campaign also promoted the lie that crime rates in the US are out of control, despite the fact that violent crime is at a 50-year low and that a splashy report claiming that massive organized retail crime rings existed had to be retracted for inaccuracy.

None of these facts seem to have phased a majority of American voters. In the exit poll, 73 percent of respondents said they were dissatisfied or angry about the state of the nation while 67 percent rated the economy as “not good/poor.” That echoed a May survey commissioned by the Guardian which found that 56 percent of adults who responded believed the U.S. economy was in a recession.

Trump’s victory was built on blatant lying, but it could not have worked without the far-right media machine that Republicans have been building for decades but which has mushroomed in size since the once-and-future president came onto the political scene in 2015.

When you compare and contrast the Republican and Democratic parties, it’s crystal-clear that Republicans have created a sleek and modernized ecosystem, while Democrats oversee a tottering coalition based on outdated assumptions about how politics works.

Democrats have great tactics, but their strategy is obsolete. This is why Kamala Harris lost.

In internet age, media platforms matter far more than policy platforms.

I hate to say it, but I’ve been afraid this would happen for a long time. This essay is part of a larger series called “How This Happened” which I started in March when I began to realize that Democrats seemed to have learned very little from their 2016 loss to Trump, and that the party’s 2020 victory was primarily due to dissatisfaction with Trump’s pandemic oversight rather than a mandate for Joe Biden.