The news is terrible. Americans are extremely divided along political and religious lines, and far-right radicals have completely taken over one of the country’s major political parties. It’s a lot to handle.

And yet, as bad as things are, it’s important to realize that they are improving. Although it may be hard to perceive right now, beginning with Generation X, every single generation of Americans has become successively more tolerant and more willing to update and expand the social safety net in ways that every other industrialized country has done so.

While Generation Z is by far the most active and progressive group of young people in decades, the older Americans who agree with them are going to have to stay in the fight to protect democracy by expanding it.

How do we do that though? It’s a complex question, a significant part of which is getting people with progressive views to be more open about challenging right wing extremism in their communities, families, and institutions, especially religious institutions.

In today’s episode, I’m pleased to welcome John Pavlovitz, he’s a writer, pastor, and activist who has personally experienced being canceled by intolerant Christians a few years ago. He’s since gone on to write several books and has a new one out that we’ll be discussing called “Worth Fighting For: Finding Courage and Compassion When Cruelty is Trending.”

The transcript of our March 15, 2024 conversation is below. Because of its length, some podcast apps and email programs may truncate it. Access the episode page to get the complete text. The video of this episode is available.

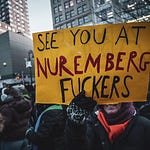

Cover photo: Andra C. Taylor Jr. / Unsplash

Related Content

Most movements to make political change fail, what do the ones that succeed have in common?

As the Republican base becomes stranger and more hateful, party elites are losing the ability to simultaneously reach it and the general public

Male popular culture is obsolete, and many men are suffering because of it

Statistics show that trans-inclusive policies don’t increase crimes against cisgender women and girls

The Christian right was a theological rebellion against modernity before it became a force for Republicans

Audio Chapters

00:00 — Introduction

07:04 — The mental health crisis lurking behind MAGA

17:48 — Religious fundamentalists have finally realized they do not have facts on their side

28:57 — The challenge of reconciling progressive values with ancient religious texts

33:59 — How to love MAGA relatives while still protecting yourself

40:34 — Understanding what tolerance actually means

42:38 — Religion should be about the values rather than historical narratives

51:39 — The world has changed less than our awareness of it, and this is frightening for people who never really paid attention

01:00:22 — The need for religious and non-religious progressives to unite around common values

Audio Transcript

The following is a machine-generated transcript of the audio that has not been verified. It is provided for convenience purposes only.

MATTHEW SHEFFIELD: So there are a lot of different themes in your book that are worth exploring and I really do think that, and this, this is a theme in some of your other works—that it's easy to see all these terrible things that are happening and conflict. But it's important also that we see more than just that.

JOHN PAVLOVITZ: Right. For sure. I think that it's really easy in the day to day being in the trenches of life and being really up close to so much that we're struggling with. And the news is bombarding us constantly with all the threats and all the things to be worried about.

And there, many of them are valid, but for me, it's always about helping people and myself right-size the threats and to realize that that is only part of the story and that there is so much beautiful work happening in the small and close of all of our lives. And sometimes it's important to remember that the, the agency that we have individually and collectively, and that's what the book and that's what most of my [00:04:00] work is about.

SHEFFIELD: Well, okay. So when you say “right-size,” what do you mean by that?

PAVLOVITZ: Well, I think many of us get up every day and we hop onto social media and we see something that alarms us or worries us and we want people to be informed. And so we share that. And then they, they share it and they repost it and then they comment to us and we get a notification about that.

Then we see it on our timelines again. And so what social media does and what that influx of media can do is artificially enlarge the bad news. So that by 9 a. m, 10 a. m, we've seen the same stories over and over again. So much that it's sort of saturated us and we can get so deflated that by the morning we want to just stop everything.

And it's important, I think, that we remember there are other, there's other evidence. There's other data that we need to take [00:05:00] in and be reminded of that to balance out all of the existential dread that so many of us are feeling.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, no, that's true. And well, and then also, I mean, you use the word existential and we're actually going to be doing a couple of episodes on theory of change about that later in the year existentialism proper.

But one of the key tenants of of existentialism is that you are the one that's responsible for how you choose to respond to the situation that you live in. And, and you talk about in the book, a lot of people have this belief that somebody's just going to come in out of nowhere and fix everything and save us from this mess. And it's a nice, it's a nice thought, but it's, it's a fantasy.

PAVLOVITZ: It is the, the, the greatest movements in history have been born out of people who looked around, saw [00:06:00] the evidence in front of them, and And decided that as dire or as disconcerting as it may be, there's something that I can do to affect that.

And those 2 sort of resources we have our agency and proximity. We are always somewhere. We always have. Closeness to a community into a group of people and to need and then we have. something that we can do to affect that. It's the idea that the arc of the moral universe, yeah, it is long and it does bend toward justice, but human beings are the arc benders.

We, we have the ability to affect the times in which we live. We're not passive participants in them. And so, whether that comes from a spiritual place or from your own morality or your own sense of identity, That's what I want people to embrace that there is always something you can do. And as you said what happens is is objective reality, but then we editorialize that in our heads and we can [00:07:00] choose how we respond to everything happening around us.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. Yeah. And what an important part of being able to choose how to respond is. Is sound mental health care for yourself and and that, and that's something that you talk about also that, the, I mean, there is. A mental health crisis, particularly for Trump supporters. And I, it's something that, it's, it's something that really doesn't get addressed in, in most of the mainstream media coverage.

Like they love, sending a reporter on an expedition to a diner in Ohio or a church in Georgia. But they don't actually, really dig beneath the surface other than to simply ask: ‘Well, do you still like him?’ ‘Yeah.’ ‘Okay.’ And nothing beyond, well, what is it that was there inside of you before Trump?

And it's an important question to note [00:08:00] because a lot of people who are, are especially devoted to Trump. They weren't political at all before because they felt like there was nothing, there was nothing there for them. And for, for whatever reason they felt that way there's just this, this profound crisis that a lot of people are in of conservative and reactionary people are having, especially in the red states. And you talk about it.

PAVLOVITZ: Absolutely. And what I find is that when, when we do have media pieces about a Trump supporter and why they're still, we still have adoration for him, why they still support him, it almost is sort of a sideshow image that the media is creating.

But really beneath that, there's a sadness there for me. There's a, an understanding that a whole group of people in our nation. Lacked a sense of community or a sense of belonging so much so that they found in this person [00:09:00] and in this movement, a place where they somehow, as you said, felt that they belonged, even if that they were embraced conditionally, even if they were being, they are being used by a group of people.

And yet. They don't seem to understand that. And that's the saddest part. And what that movement has done, both politically and and religiously, it's leveraged the worst of people's fears and phobias and prejudices. And so you have a group of people who are not just. embracing a movement, but they are being weaponized to fear other people.

And I think the worst of religion and the worst of politics requires an enemy, an encroaching adversary. And that's the mindset that so many people are in. And it's just when people, no one is at their best when they're terrified, I think.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. No, true. And, and the other thing about it also is that the, the, the sort of panic [00:10:00] response that they're having, it is it, it, it makes them behave well, and they, they're choosing to behave and that's, let's be clear about this.

Everybody has agency, they're, they're responsible for their own actions as well. But, the, the, their actions that they're engaging in oftentimes are so repellent and so, awful that the natural inclination is to just. Get away from me. I want nothing to do with you. You people need to.

Go away and, and, and, and like, and, and, and it's even cropping up especially I think also in terms of, of romance especially between in the, in the heterosexual sphere where, there is a significant political divide that is emerging between women and men. And you see it on, dating.

So I hear from women all the time. They're, they're like: ‘I keep getting approached by these awful Trump men who don't understand what I think at all. And they don't want to understand me and they don't care.’ [00:11:00]

PAVLOVITZ: And that for me, Matthew is the real story here as someone who has worked in-- I've been in local church ministry for three decades, but now doing this work as what I call a collector of stories. And I hear from people, hundreds of people every week. And what has really surfaced from the pandemic. And then from everything of the tribalism, we've sort of been living with for the past 8 years.

This is really a relational crisis. There's the political side of it. And there's the, theological side of it. And aspect with the church, but this really trickles down into the relationships we have with our families and friends and coworkers and neighbors. And that is where we're going to have to reckon with all of this because it's where it settles into really where the rubber meets the road of our lives.

And so many people are living with a, with an extremely different feeling about their, their tribe of affinity that they [00:12:00] used to have.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. And, and, and a lot of it is. It is, it's the product, it's the product of decay or disinterest by institutions that should have been there for them. And, and and we'll talk about the religion side of it in a second, but you know, like, I think that people who are have a left of center perspective often correctly note that the, the The Republican voters are kind of going against their own interest, to use a phrase that's often used.

But at the same time, they're doing it because they feel that what Republicans are offering them is their interest. In other words, their interest has changed. And so their economic interests may not be benefited, but they have, they have been made to want something different.

And yet at the same time, the anger and angst that they feel is actually the product of the Republican party because they don't actually care about their voters and they don't take care of them in terms of, funding for mental health care or [00:13:00] funding for healthcare period, or, not having job training programs for people who are displaced economically for a variety of reasons, and trying to cut out things like social and emotional learning in schools because, those programs are really, really important right now, especially because a lot of people are not interested in, religious institutions that you have to give them some sort of tools.

To deal with with adversity in their lives, and the right wing is is trying to make people not have those tools.

PAVLOVITZ: That's right. And when you when you inject that fear into a person's emotional systems, and they're going around every day, believing that there are constantly, Adversaries and enemies around them.

And then you have a movement that says, we'll take care of you. It, the details don't really matter. And I think the Republican party has done a great job of creating a mythology that people will simply [00:14:00] embrace. And, and that's, there's, that's a product of things like our critical thinking, breaking down and people's just lack of general knowledge about civics or what's happening in the world.

Or, partisan media, which takes out any bad news or any differing news to the story that they tell themselves. And the end product of all of that is a group of people who will embrace the, the lie that Republicans care for them. And when really there's zero compassion in that movement, and that's what's been Startling to me as a minister for all these years is seeing a cruelty, a movement of cruelty rise up in the evangelical church and in, conservative politics that is simply predatory.

And, and what I'm always trying to let people on the right know is that I'm for them. As well, I'm for their families. I want health care for, for their families as well as my own. I want to clean planet for [00:15:00] them as well as my family. And that's a hard thing in the, in the tribalism to, to hear,

SHEFFIELD: It is. And your point on that is, is really, really important because ultimately, the, the vast amounts of anger and loss and loneliness that, that is really what drives Trumpism it exists because, conservative institutions, they failed in what they were assigned to do. And, and that's a lot of that is on the, is on the, is on the traditionalist church and, and I mean, in terms of that, they haven't learned to evolve with the times.

So, I mean, like in many ways. We're dealing with the, our, our society as a whole is dealing with problems that were controversies that existed in the, in the early 20th century. Like, they, those were problems, that were debated by. Whether it was [00:16:00] Nietzsche, or Kierkegaard, or, these, these early 20th century philosophers, they saw this crisis of meaning much sooner than the rest of the world did, and, and they were writing about it, and, and, and Nietzsche also, I think, people, because of his sister kind of, um, she was basically a Nazi and kind of rebranded him, but you know, like so much of his work was, saying to people, look, what you derive meaning from is over.

And you cannot go back to it. And, I think that, that realization, It took a hundred years for everybody to finally have it. And, or at least in even maybe intellectually, they don't have it, but, but psychically, psychologically, they do have, and that's the moment that we're, that we're having right now.

PAVLOVITZ: It's some days I think for people like myself and possibly for you, many of your, your listeners and, and viewers is that there's a disbelief that [00:17:00] we're, we're Having these conversations and this struggle seems so profound that so many people seem to be pushing back against ideas that we felt like were now fixed parts of our society.

And just even the ideas that someone could marry the person they love, or a woman could have body autonomy voting rights, all of these things that felt like givens and maybe left us feeling a little falsely, that we had made more progress than we had. And, but now there's, there's an awakening, a disbelief that so many people are feeling and trying to decide, how do I find myself in this new environment?

What is my place? Where is my identity? And so it's happening from, both sides of the political aisle per se

.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, well, and and just to go back to the religion side of things I mean, there is, there's, There's a real crisis. I think that like, I mean, when you look at surveys of Americans, a [00:18:00] large percentages of them have always disbelieved in evolution.

Even though it's been a scientifically proven for more than a hundred years and but it's, it's like, it's finally, They finally realized that they lost this because like before, let's say in the 90s, 2000s when the Internet was, first becoming sort of, completely mainstream and pervasive.

They really thought that the facts were on their side. They really did. And, like Ben Stein, for instance, the the right wing actor, he made a movie called Expelled, No Intelligence Allowed. which purported to, was a case against evolution. And I really actually encourage people to watch that movie because it's, it's so illustrative of this mindset and, but he, he put it out there and they all thought it was so great, but everybody else just laughed at it and thought it was absurd and, and stupid.

And like, That sort of thing [00:19:00] happens, has happened in so many people's lives. Like it used to be the case that people could say, well, like evangelical churches, they had tremendous growth in the United States for many decades, and they were always boasting against.

More mainline Protestantism or Catholicism that, Oh, you guys are headed for the grave. No one likes you anymore. You're losing all these members. We're, we're, we're going to win all this. And things have now actually reversed. That liberal Protestantism is now the one that's growing and evangelicalism fundamentalism is just collapsing.

And you said something, you wrote something in the book that I want to talk about in particular on this point. You said that. Honestly, I don't know if organized Christianity on balance is helpful anymore. I do know is that the compassionate heart of Jesus, I find in the stories told about him is helpful and urgently needed.

How is that perspective kind of terrifying to a lot [00:20:00] of Christians? Would you say?

PAVLOVITZ: What you wrote there, it probably is, but I think it's one of those questions that that many people of faith who are left leaning ask themselves all the time, because what progressive spirituality of any kind really is a willingness, as I say, to fight with and for our faith traditions to be ruthlessly critical of them to challenge them and to trust that the answers are going to be, Something that we can live with, but there is a sense of lostness or, or homelessness that comes when you look at the tradition of your past and you discover realities about it.

And then you have to decide, well, who am I now? And for me as a minister, that was where the journey began really asking hard questions about theology toward sexuality and toward racism and toward gender equity. The answer is I didn't like what I was getting because I had built my whole [00:21:00] life on this myth, this evangelical or this mainstream Christian orthodox understanding, at least in America of, of people's color of the marginalized.

And so now I'm in a place where so many others are is trying to decide how much of this faith can I hold onto? And how much of it do I need to discard? And what do I do with what's left? How do I identify?

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. No, and that, and that, that's what's terrifying, I think, and that's what's driving a lot of this traditionalist Christian rage against everybody that, they don't, they don't want to have these thoughts.

These thoughts are, are dangerous. Mentally, they are, and, and what, or at least they seem that way. Like in my case, I was born and raised in a very fundamentalist Mormon family. And, and I had all those beliefs. I I believed that, I had God, God gave me revelations and I wrote [00:22:00] them down.

I was all in for this stuff. I read the Bible and all the other Mormon books in their entirety by the time I was eight and many times subsequently, so like, I really believed it and But at the same time, so I, I, I left that tradition when I was 27, there were still throughout my, my life up until that point there were always these little things that I noticed along the way and, and people would tell me, don't notice those things.

Don't think about those things. You need to put those away. Those don't matter. You'll find out someday in heaven, God will explain it all. And, and, and that worked for me for a while. But then once I, once I realized it's okay for me to not it's okay for me to decide what I believe is correct.

I don't have to do what other people tell me. And like, that's, I think that that moment for, because many people, for [00:23:00] them The value of religion is, is answers. And it doesn't matter if they're good answers. It doesn't matter if they're healthy answers. It doesn't matter if they're kind answers. What matters is that they're there.

PAVLOVITZ: Well, and exactly. And what I usually say is most people want a shorthand religion. They want a group of scriptures that they can kind of pull out when they need to. They can be told. What they're to think and feel about these big issues and that those things can be settled and they can attend a building for an hour on Sunday and then go on with their lives.

And as I said before, that the existential crisis, most people don't have the time to go through something like that. And it's necessary. And I, I, I didn't intend to be a minister. And so I entered into the church, not realizing that this was going to be a position where I was going to find myself.

And yet it made me keep asking those difficult questions. And you're right. Certainty was sacred in so many of the communities that I was a part of. And [00:24:00] doubt or questioning was some sort of character flaw. And it was only when I really. Realize that whoever and whatever God would be would not be intimidated by my questions.

Only people are intimidated by questions that I pushed into those things and began writing and speaking and preaching about them. And that's when the trouble comes because people are threatened not by something you say. Usually they're threatened by simply saying, well, is that possible? Could you be wrong?

The existence of hell be incompatible with the character of a loving God, and could women be actually equal to men and have their gifts be responded to in a spiritual community? And once you begin upsetting that, that turbulence comes and people will run away from it.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. Well, and that's because, I mean, for me, I, I think that, that everybody wants to be seen, but most people don't want to be known.

And the one, and the, oftentimes the, [00:25:00] The most terrifying person to be known by is yourself.

PAVLOVITZ: There are those I think speed and activity in our lives can always mask a lot of things. And so when you see people who are running all the time and their lives are busy and they are busy because there's important things happening, but that can also anesthetize us from those deeper things that we don't want to give time to.

And you talked about the sort of mental health crisis. And I've written about what I call the mental health crisis of MAGA America in that, There there's a whole section of our population who not only rejects science, but rejects the idea of therapy and medication and mental health care. And those things are somehow some, moral failings.

And that's contributed to a large group in our population who simply haven't. They don't know how to process their feelings or talk about [00:26:00] their angst, especially men, as you, alluded to earlier, there's a divide here along gender that men have been done a disservice by their politics and their religion.

And it's now being shown tremendously.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. Yeah. It's, it's really unfortunate because, it's basically making like right wing people often, try to. They talk about sort of the, the product, which is, a decline in marriage rates or decline in birth rates. And they, and they get very upset about it and they blame, almost anything for it, whether it's, chemicals or gay people or, whatever it is immigrants doesn't matter, but like what they, what they don't want to admit is that, that many men, especially let's say 30 and up, they don't have the tools.

To process the reality in which they live and, and, and, and that, and that they don't understand that [00:27:00] when the feminism has won and women are never going to go back and they don't have to go back and they should never go. And so if you can't accept that, then, you're going to have problems in with reality and you're going to hate everyone and you're going to hate yourself.

And that's terrible.

PAVLOVITZ: Sorry. And then there's an irrational response. So it's not really people don't even know why they're angry, what they're angry about. We were at the airport not long ago and it was like one of the news stories. Some man there just got frustrated by whatever he was frustrated by. And he started screaming and ranting and raving and running around.

And singing amazing grace and all these very bizarre things. And I looked at him and people were of course, laughing and filming him. And all I thought was this, this is a 60 year old man who still doesn't understand how to process his emotions and how terrifying and sad is that? And and, and you're right.

When you look [00:28:00] at the often with conservative politics. And religion, I always say that the attack is an inside job. It's a, it's a lack of being willing to look in the mirror and say, well, what are we contributing to this problem? And for me, Compassion and courage are so huge in the book, because I think that's what we're lacking in so many men who are conservative, they, they, empathy is, A lost art and then the ability to offer a differing opinion.

You know what, when I was steeped in the, in the religious world, in that evangelical world, it was so fiercely protected. I always say organized religion and organized crime are very similar because they're fiercely loving when you're on the inside, but there's such a terror of, of being pushed to the periphery or excluded altogether that people will do anything to stay in there.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, they will. And, and [00:29:00] kind of related to that, to some degree, I feel like also with this religion sort of unprocessed, reality that many churches are dealing with is that, there are progressive religious traditions that they, they, they do support women's equality.

They do support, LGBTQ relationships and identities. But they, but they, they are not telling the full story in that they try to say that the Bible supports these things. And the, the Bible says it's okay to be trans or that, it's okay to be gay. And, if those answers are, they're very unsatisfying for a lot of people. I, and I, I think a lot of progressive people, theologians or ministers, pastors, rabbis, I don't think that they understand that, that when, that when people think that you're lying to them and because the reality is, like these traditions, they're not making it up, like right wing authoritarianism has all kinds of [00:30:00] scriptures that they can cite to and all kinds of historical contexts and all kinds of.

Saintly authorities or commentator authorities. They're not making this up that they And, this is not some invention and people, it didn't come out of nowhere. Like, this is real, and to pretend that it's not, it's insulting, I think.

PAVLOVITZ: And I think that's where you see, for me, Matthew, is over the last few decades, as the religious right has so commandeered, theology, spirituality, religion, a whole group of people who are moderate left leaning and have spiritual inclinations of some sort, have simply quieted and yielded the floor to this one stream of theology.

And because it is a messy thing to say, for example, for myself, I started with simply the six or seven verses that were so used the clobber versus to attack people who are LGBTQ. And I dug deep into [00:31:00] those and studied them to find out what the context was and how they were being used. And I came to find out that they were being weaponized completely inappropriately for the conditions in which they existed.

And yet that didn't just mean I was taking those six or seven verses because now I had to ask questions about the words to either side of those verses and to the books they were a part of and to the entire library of the scriptures. And most people As we've been talking about simply don't want to do that on the right or the left.

It's much, it's difficult to say this massive sprawling thing that I have embraced may not be what I thought it was. And what am I going to do about it?

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. Well, and and, and I don't know, it's just like when you, when you're trying to get into, Bible bashing with people who disagree with you.

Like, I mean, the reality is the Bible is such an immense book. and written by, hundreds of [00:32:00] people literally. And, so it, you can pick out any verse to say whatever you want it to say. And so at a certain point you have to understand that, really what these differences are, they are philosophical differences and they're more than they are theological.

And you have to be willing to admit that. And I think a lot of religious people are not there yet, but clearly you have gotten there.

PAVLOVITZ: And for me, whatever the, I call myself a spiritual mutt at this point, I have been at every sort of spot of belief or place of understanding. And what I've come to the realization, and I think many people have, whether they are religious or not, is that your faith, your spiritual beliefs only exist relationally. That's the only way they, they really manifest themselves. And so your theology is really irrelevant to people, especially younger generations who don't aren't steeped in the stories or the [00:33:00] mythology or the orthodoxy. And they're saying, well, what kind of life are you living?

Because they don't really care what you say you believe. And so your, your theology is only valid to the degree that your life is loving. And. So that for me is where the, where the whole thing nets out. What are people experiencing and what you have in the religious right is a group of people saying.

Well, yes, LGBTQ people are telling us we're hurting them, but we're not hurting them. And the women are saying we're being subjugated and we're saying, no, you're not. And it's, so it's a lack of listening to the oppressed or the maligned or the discriminated against. And simply choosing not to hear them in the name of a God of love.

And so that's where it all begins to break down. And it's just frustrating for someone who is not grown up in that environment to even relate to them. So there is just that, that chasm of communication that exists now.

SHEFFIELD: Uh, [00:34:00] yeah. And, and certainly in the, at the interpersonal level as well. And you talk quite a bit about.

That in the book and a bunch of, of chapters and especially on the idea of, how can you, how can you love someone that is toxic? I think that that's, that is a, a, a thing that a lot of people are struggling with now that, they have relatives who, might be virulently anti gay or, or whatever it is.

And yet they still, they still are there and you still do love them. I mean, so let's tell us a little bit about some of that.

PAVLOVITZ: Well, I mean, gosh, hundreds of times a week, people are sharing their stories with me via email or video chats or texts, and they're saying, this is where I am.

I am married to someone who I've been married to for 37 years and suddenly I don't feel like I know them. And so I never want to be [00:35:00] cavalier with people's deepest relationships and say, well, okay, just say goodbye to them and begin to craft a different kind of community. Sometimes that's necessary. But the truth is.

That's what part of the book is, the fighting for America, for the church, for marginalized communities, but it's also fighting for our relationships, and for the people that have been a part of our families and tribes for, since we were born. Those things aren't easy, but To discard and nor should they be.

So it's trying to figure out in each relational exchange, is this still possible to save where, where is the common ground? Or in some cases, do I just simply have to love someone from a distance and realize I can love and respect their humanity, but not want that kind of relational proximity to them. So it's, it's a daily battle to figure out how to wisely yield, Well, I always tell people we're in the tension between our relationships and our convictions all the time.[00:36:00]

And it's how, when do we choose one versus the other is a real challenge.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. Well, not to put you on the spot, but what are a couple of stories that kind of illustrate the approach that you are advocating here?

PAVLOVITZ: Well, I've got a, a good friend. Her name is Susan and I talk about her in, in this book.

And during the 2016 and the fallout of the election, Susan said, I'm disheartened by everything I'm seeing and the tribalism and the animosity, and I want to do something about it. So she decided to have a bunch of women over to her house every week to play bridge and have lunch, but to intentionally talk about the topics of the week that were making the news.

And these were women who were Diametrically opposite her theologically and politically, and that was a case where she invited this turbulence very close and for a long period of time, and it's been very difficult. But what she's been sharing now. Seven years into this is that [00:37:00] there there's true relational intimacy happening vulnerability.

That's allowing people to say, here's, here's the heart of where I am. It's not just some drive by social media exchange. It's something substantive. And I think that's the only way we're going to make any headway is really meeting people's humanity and respecting their story and learning that story. I'm a firm believer that the more we get to know a single human being, the better it is to understand them.

We may not like them after that. We may not agree with their politics or their theology anymore, but we're going to see them as a fully complex human being. And I think we continually have to remember that. And also that there are these universal experiences that we're all having, grief, loneliness, and fear, And whether we're to the right or to the left, those forces are always pushing on us.

So if we can recognize the universal grief and loneliness and fear in the other, [00:38:00] maybe we can meet them in a place where we can, we can reach them and have an understanding.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, well, and one of the other points that you make in this regard though, is that that a lot of times people, you have the expectation that. Love requires physical proximity, and I'm just gonna quote, quote from the book here. You said, you wrote loving another human being doesn't necessitate you placing yourself in harm's way.

It doesn't demand you sustain, sustaining repeated wounds, and it doesn't require you to make peace. With what you cannot abide. The biggest misconception people have about love is that they owe people they care for permanent proximity. They don't. That isn't love's expectation, despite the way we are guilted into believing.

PAVLOVITZ: And, and that idea of love, it's so easily weaponized or the idea of tolerance related to acceptance and love. [00:39:00] I. I hear every day. Well, John, you're from you're a leftist and how you're supposed to be so tolerant. Where's that tolerance when it comes to these things? And it's simply that's a semantic use of words to try and dismiss you.

But for me, it's really about, there are things that I will not tolerate and it's my willingness to dig in and find those hills worth dying on and declare them. I don't want to lose relationships with people I love or people who I've served at my churches. But if that's the cost of my authenticity, and if it creates in me a desire to speak explicitly on these matters and help someone else, then that's, that's worth it for me, because that's the other part of this.

So many decent human beings, I think, are intimidated And they don't want to enter the fray. They don't want to be in that messiness that is required when social change needs to happen. And many people are just [00:40:00] busy or simply too tired. And I respect that. And that idea about love and proximity is important because I think we can all be guilted into believing we have to keep trying when sometimes we're not in that place where we can.

And I, I always want people to respect their, Current condition. There are days when I feel like I can enter that fight or, or try again with a person who I love. And there are days when I can't because it's creating too much toxicity in me and I need to step away. So there's an ebb and flow to this as well.

That's that we need to respond to.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah.

And it's, and the word tolerance is an interesting one because in the, in the denotation that we're using it here it's actually a metaphor. The, the original meaning of tolerance. refers to metal, how it can bend and yet not break but still be hard. And that's That's really what I think is, is what we should think about [00:41:00] tolerance in this modern age here that, you can be as strong in your convictions as you want to be, and you don't have to break them.

But at the same time, in order to exist in some fashion or another, and that's entirely up to you to be able to bend. I think that's. Something we're thinking about

PAVLOVITZ: And, and deciding how, how much will I, will I tolerate in this context? And how much, when does the moment come where I need to separate myself from this?

Because for me, as a minister, I found that there was a dangerous ambiguity that I. That I engaged in because I knew what I felt, but I knew what my people could tolerate and language. And so I would nudge them to a certain point, but I knew if I nudged them here, it would be too much. And that's one of those places we do that in our relationships.

We say, well, I don't know if I can push back here because if I do, it's going to start this whole chain of events and this [00:42:00] conflict. And it's for me, it's really worth it. The key for all of this to me is to humanize the other person. So I can disagree with someone. I can even decide that I need to cut ties with them, but still see their humanity.

It's the moment that I dismiss them or create in them some stereotype or some caricature that dehumanizes them. That's when I've, I'm in a dangerous place because that is what I see on the right so much. They've been able to discard the humanity of so many different kinds of people, and that makes it easier.

To hold the positions they hold and to yield the theology they do.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, I think so.

And you have a section in the book that you call the church. We really need what what.

PAVLOVITZ: Well, Matthew, this is, these writings come from constantly trying to figure out what, what is the church to us? [00:43:00] And the church for many people of faith, the church with a big C is just the global gathering of people. When I asked that question talked about earlier, is Christianity helpful? It's asking the same thing.

What is, what is the church to people? And there was a story we always told ourselves earlier in our lives that the church did this and did that. And it was the center of the community. And now it's, it's looking and saying, well, what is the, the net result of organized religion? And can we have churches That are known for their empathy, for their generosity, for their diversity, rather than being known as exclusionary predatory environments, which is what they have become to be known by so many people, either because they've experienced them that way, or simply because.

The religious rights prominence has created the false image that that is the only kind of church that exists. So to younger people, to people who have walked away from faith or [00:44:00] never stepped into it, that's made easier by people thinking, well, this is the only kind of Christianity there is. So the questions I'm asking are, as people gather collectively, in a spiritual community, how can they do it in a way that does no harm?

And if we ask those questions, maybe we're going to be better believers in how we practice.

SHEFFIELD: Well, and, and I mean, and specifically, what do you mean by that?

PAVLOVITZ: Well, people will talk about anger, for example, and growing up, I heard about righteous anger, that I, we are Christians, we have righteous anger.

And then I realized, well, everyone who has ever been angry, believes their anger is righteous and their cause is just. And so then. I wanted to replace righteous anger with redemptive anger. So, to say, what is the result of my anger? Does it lead to more people finding acceptance? Does it [00:45:00] yield to civil rights, human rights for more people?

Does it lead to greater compassion? Are more people fed and healed because of The things that I'm driven to do as a part of my faith. And if more people are not helped, I have to seriously ask if this is really worth my time. And the constant question I ask, people of faith is why do you have faith?

Why do you believe it's worth having? And what are the results of your faith that you can point to that it is an asset to humanity? And to be specific. And sometimes they really can't, sometimes it's really the idea of what I always thought the story of religion was, or what I was told faith was it's similar to America.

There, there comes a time when our myths that we grew up with about these things are exposed. And so we have to decide, well, what do I do now? Do I abandon the thing or do I alter the thing so that it is better than it was before or better than [00:46:00] it actually is?

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, well, and again, and then it's another sort of terrifying thing to contemplate, because those types of conflict, like they can exist within yourself within your relationship to somebody else, like, let's say, I mean, in the interpersonal level, discovering a something about somebody that you really didn't know about them. And it's so different from what you had expected and, being able to say, well, is this really why am I mad about this?

Yeah. It really is tough. And that's certainly true within a lot of religious traditions, that what is it that you're there for? Are you there for the values? Or are you there for the history book? And a lot of, I think a lot of religious people need to answer that question in, and they don't want to. It's scary.

PAVLOVITZ: Right. When you, when you answer it, honestly, well, that leads to [00:47:00] It often leads to grief. I talk a lot about grief in grieving the old story, and if we really begin to ask critical questions, and we answer them honestly, as you said, we have access to so much more information than we ever had than our parents had, our grandparents had, and so, We can have a mindset that's more expansive, but along with that comes a grieving of the old story, maybe a letting go of the former community that we were a part of.

And so there, there is, it's a frightening thing to say, even if I'm going to hold on to some sort of personal spirituality, where can I do that now? That makes any sense. Where's my sense of place. And so in my travels in person and online, I'm meeting people who are saying, I simply feel like I've lost. A sense of home in my country, in my church, in my family, and that is a huge societal challenge for all of us.

SHEFFIELD: It is, and [00:48:00] something that is interesting and relevant to that point because of the, horrible legacy of racial segregation in the American Christian community. A lot of white Protestants in particular, they have no familiarity with the black Protestant traditions that exist. And they don't understand that, the black Protestant traditions, they've dealt with a lot of these issues, a hundred years ago, 150 years ago of how can you exist in a world that doesn't agree with you? And that doesn't see you and like there, there's so much incredible theology coming out of the the black tradition and I would really urge, a lot of white Protestants in particular, but if you feel this way, black people have had these problems a lot longer than you have. And you should, you should read what they think about that.

PAVLOVITZ: I think what we use, we hear and see and use the word privilege a lot, but [00:49:00] what privilege is in this context is never having to have had this crisis that says, what, what is the world, what is my faith and how does it.

interact with the world and is the system that I'm a part of creating more harm than it's, than it's alleviating. And that is something that for white people of faith is new for many of us to ask these questions historically, because we've never been challenged to ask them. It's always been the assumption that we're on the right side.

And that's the other thing. There is just a terrifying sense of, wow, I'm, The stuff I've built my life on for decades, it's all up for grabs. And some people's response is to press in and some people's response is to avoid and distract and explain it all away and become hardened. And that's what you see the differences.

I think in the right, [00:50:00] the right is responding to all these questions and challenges and saying, it must be something else. It must be immigrants. It must be LGBTQ people. It can't be. White, cisgender, heterosexual Christians who were born in America and raised Republican. And that's, I can understand why you would avoid that if you fit those categories.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. It's easy. It's easy to think that way. Yeah. And it's tough to want to recognize that you have advantages. As a person that, have enabled you to avoid thinking certain, that's what it comes down to.

PAVLOVITZ: It does. And we have always had the, the life of least resistance. And so once you have all of these questions and all of this turbulence, you begin to think the world's changing. And it's not that the world is necessarily changing. It's that you're having things revealed to you that were [00:51:00] not revealed to you before.

And that's constantly. Kind of conversations I'm having with even people saying, well, I'm trying to understand sexuality, but it seems like there's so many more people coming out now. Why is that? Well, it's because they're not as terrified in some cases as they used to be, and they're learning. Society is learning how to accept a more diverse understanding of sexuality and gender orientation, all those things.

And so, that's the other part of this. It's helping people see that this is not something new that's suddenly happening. You're just seeing it for the first time and there's going to be some difficulty in even in that.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. Yeah. No, it's no, that's a great point that the world, to the extent that it's changing, the things have not changed as much as so much as your perception has expanded is really what it comes down to. And for me, when I left Mormonism, like that, that was really the thing that, that I can relate to that because, I had been, [00:52:00] because for Mormons, you're instructed to never read anything critical of the church . It's worse than marital infidelity in many cases and to read it, to read a, a former Mormon's book or something like that. And it's advantageous to the church or, the local leaders to say things like that. And understanding that people have an incentive to tell you not to read other people like that.

That's the thing that is always interesting to me. I always hear people say, well, you don't want to debate my ideas. You don't want to talk to me. I'm getting canceled for saying things. And they don't understand that. Well, actually people debated your ideas a hundred years ago and you're a side boss. And so we don't need, we don't need to hear your, your, your you don't, we don't need to have your ideas about, the 6, 000 year old earth and the schools.

We don't need to have your ideas about that homosexuality doesn't exist or that trans people are not real. It's just a mental illness. We don't need those things because. Transgender people have been [00:53:00] around, since the beginning of humanity and, and there is ample historical record to indicate that and, but you just don't know about it.

And your ignorance is not an argument is what it comes down to.

PAVLOVITZ: That's right. And for years, I think, Especially a white male Christian was used to being able to speak their minds unabated and unchallenged. And, and, and even when you look at the evangelical church, I think we've been closely tied to many organizations that are doing, who are now really instrumental in perpetuating this toxic Christianity, your, your Franklin Graham's, your things like that.

And what are found in those places. Was that they, they simply didn't allow, I speak all over the country. I have for a decade now doing this work. I've been invited by progressive churches, by humanist conferences, by [00:54:00] synagogues and mosques and atheist conventions, but I rarely. Really almost never been invited by a conservative church to come and simply have a discussion about the things we're talking about today, because there is such a control that's being exerted over the people there because they're terrified

SHEFFIELD: of you're terrifying.

Yeah, yeah, terrifying. That's really what it comes down to. And. But they're, and they're so scared of you that they can't even say that also.

Like,

PAVLOVITZ: yeah, that's right.

SHEFFIELD: Is the, like there, there are, are all these people out there that, are making millions and millions of dollars saying, Oh, I was a former progressive. And now, I love Donald Trump, like, Matt Tybee, or, some of these other out there and they never want to have actual debates with anyone. And the same thing is true, in the evangelical world, same thing is true in the, in the Mormon world. None of these people actually want to have a discussion of ideas.

What they want to do is [00:55:00] bully and call it an argument.

PAVLOVITZ: That's right.

They want to have a. Be in front of people and have a monologue that just hits the person over and over again with the talk, with the talking points and the critiques that they've gotten so used to throwing out there in social media world, and they don't really want to have a conversation.

And that's the sad thing for me, being someone who still has a heart for some of the tradition that I come out of. It's realizing that It's actually a better place. I want people to experience that expansive understanding of the world that you, you can ask questions. You can challenge ideas and it's okay.

And it's looking at a group of people who simply have sidestepped that altogether is just really sad to me because it means you really don't believe. What you say, you believe you're actually really worried. I talk a lot about how conservative Christians talk about this God who is [00:56:00] so all knowing and all powerful.

And yet that God seems really neutered because they're so terrified of everything. And if God were as powerful and loving as they say God is, there wouldn't be as much to worry about as they seem to be.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, no, absolutely. Well, and let's maybe end on two points here that trying to have that, that dialogue and, and being willing to, somebody who is, um, religious progressive I think a lot of religious progressives, they, and, and people would have told me that, that this was their viewpoint.

PAVLOVITZ: So I'm not just, making it up, but, and I'm interested in, and if you've heard this as well, but, Like a lot of religious progressives seem to think that, well, people will figure it out on their own. They will see that I'm right. And I don't have to advocate against these other people because they're just so obviously wrong.

And, and when people look at my material, they'll see that I'm right. And they don't understand that number [00:57:00] one, the, the followers of these people will never see your material unless you bring it to them. And then number two, why would you want to consign people to these, toxic churches where they are manipulated, where their money is stolen from them, where they are lied to, where their epistemologies are destroyed.

You Why would, do you, did you have any compassion for your fellow Christian? Aren't you concerned about them? Wouldn't you wanna save them? They deserve to be saved, don't they? That's what I would say

it, it's, yeah. Go ahead, Matthew. It's, it's the, it's that, but it's also, there's a point where I might allow someone to remain in their, their ignorance, intellectual ignorance or their.

They're toxic theology, and it's one thing to leave them with it, but I'm also leaving generations of people that they're existing around and damaging and influencing. So there's also that part about it to see for me, I [00:58:00] I've been so grateful for the power of social media because I was simply writing some words and those words were released into the world and those words could find the people they needed to find and challenge them.

And that's what I've, I've discovered is I need to speak specifically, not just to change the mind of the bully, but to stand with the people who are being bullied. So there's a, there's a dual purpose to the work we do in the world in this way.

Yeah. And, and I would say, for, I mean, people can, they're entitled to believe whatever they want.

And, but for, if you are, people need to, who are, our, our political struggles so much are the product of the fact that people do not distinguish between, Authoritarianism and conservatism. And it's the conservatives who, who allow this, their identity to be stolen. They have allowed, authoritarians to pretend to say, oh, I'm a conservative.

They have allowed that to [00:59:00] happen. And, and as a result, they've, they've taken over and they bullied the conservatives to be this little tiny rump. Of nothingness in the Republican party. And, they canceled and destroyed conservative evangelicalism and just stamped it out of existence almost.

And because the conservatives didn't stand up for themselves. So like, that is one thing that I do appreciate that you're doing to say, look, guys. Do you value your ideas? So you need to fight for them. Because no one's going to do it for you. And if you don't, you're going to lose

for sure. Yes. And, and they're, and they're seeing that, I think if the 2016 election goes differently, this.

Conservative religious evangelical right wing Frankenstein monster was on its last legs. And what it had been has been given over the past few years is a power and a voice that it hadn't really had. And I think if we can survive this time and get past this sort of [01:00:00] urgency, younger people, as we've been talking about, they're going They're decided these issues of gender equality and sexuality and race, so they're not going to be bogged down by those things.

And if we could just steward the nation and the world to keep them, having control over their bodies and their votes. Then I think we're going to be in good shape.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, no, I think so. I think so. And let's maybe end with the topic of non religion. So, you're still a believer in God but a lot of people aren't, and, I think a lot of people who are not religious, they have a faith of their own that religion is just going to go away, and everything will be perfect after that happens.

And it is really naive because religion isn't going to go away. You're not going to get rid of it. It's not going to be destroyed on its own or ever. Probably people want to believe in a higher power for whatever reason, it seems evolutionarily we [01:01:00] are wired in some way, so many of us are. And so you have to realize that in the same way that right wing atheists have understood that, they need to make common cause with right wing believers, I think left wing atheists need to understand that as well. So you've, you've mentioned some of your experience on that, but let's maybe talk about

that a bit here.

PAVLOVITZ: I think that's been the most gratifying part about doing the work that I do is. Is creating the writing has become a hub for people who may be religious and non religious, but they're saying, Hey, there's enough here that we agree upon that we can formulate a sense of community. And those are things about, the fragility of humanity and the, the.

The interdependence that we all are a part of. And so those are really, whether you're a theist or not, whether you have spiritual leanings or you don't, we, we can align around things that are redemptive and productive. And so [01:02:00] that's, what's going to have to happen because this is not a, the fight is not religion versus atheism and it's not progressive Christianity versus conservative Christianity.

It's, I think, Empathy versus cruelty. It's, can we see our neighbor as a part of that? We're tethered together or that were enemies that were separate. And that's what you see. That's what we're fighting for is a group of a community that says we actually are better together than we are separately.

And those divisions are never going to be healthy. And so that's the work that I'm trying to do with the, with the book and with the writing and everything I do.

SHEFFIELD: All right. So yeah, it's been a great conversation, John. So for people who want to keep up with you, what are your recommendations for that?

PAVLOVITZ: Well, once you know how to spell my name, which is P A V L O V I T Z, there's not a lot of John Pavlovitz's around.

You can pretty much find me on any platform that you need to. I'm [01:03:00] kind of everywhere and would just look forward to conversations and, and questions and dialogue.

SHEFFIELD: Okay, awesome. All right. Well, thanks for being here today.

PAVLOVITZ: Thank you. Such a great pleasure. Matthew.

SHEFFIELD: Thanks for joining us for this conversation. You can always get more if you go to theoryofchange. show, where we have the video, audio, and transcript of the episodes.

And if you're a paid subscribing member, thank you very much. You have unlimited access to the archives. And if you can't afford to subscribe right now, I understand. very much. You can help out the show. Nonetheless, if you go to Apple podcast or Spotify and leave a nice review there, five stars as short as you want just some sort of writing on it.

That is really helpful to get people to get recommended to watch or listen to Theory of Change.

So that will do it for this episode. I hope you'll join me next time. I'm Matthew Sheffield.